Music Distribution

We are currently experiencing some short-term hiccups with our physical CD distribution: in the meantime please click on the album links on our Albums page and hit the Amazon buying links to check if your title is available .

Download sales continue to be available via the usual services and you can also still stream our music as usual.

Music Distribution

We are currently experiencing some short-term hiccups with our physical CD distribution: in the meantime please click on the album links on our Albums page and hit the Amazon buying links to check if your title is available .

Download sales continue to be available via the usual services and you can also still stream our music as usual.

Quadraphonics And Music

Surround Echoes from 1974:

“An appraisal of the musical possibilities of quadraphony, and some speculation about potential future developments”

by Michael Thorne

Features Editor, HiFi News and Record Review

first published in HiFi News and Record Review Annual, 1974

‘…back to mono.’ – P. Spector

‘The music of the future is directed towards a third ear.’ – F. Nietzche

Although the technical merits and otherwise of the various quadraphonic disc reproducing systems have been exhaustively argued (with, one hopes, some progress toward an eventual standard) the problems facing the record producer confronting the new medium are similarly fraught, not to say intimidating. Suddenly, the entire activity of music recording has to be reappraised, which gives rise to a polarity of attitudes even greater than those current on the technical side. Before attempting a summary, it would be as well to remember how we have come to the present stage.

Leonard Bernstein and the London Symphony Orchestra recording Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring in Abbey Road, Studio 1

Until the extensive introduction of four-channel recording, successive progress through mono and stereo was a progressive relaxation of suspension of belief. The listener was (and still is) helped by aural conventions which grew out of necessity. The single mono source had reverberation spread in a narrow line behind it. Stereo broadened this out, but the illusion of depth was maintained in order to suggest to the listener that he was somewhere else, or that his front room was somewhat larger than it might appear. This was additionally helped by the possibility of random phase differences between the two channels, which caused more attention to be paid to reverberation. As well as receding layers of perspective, we then head a lateral displacement corresponding to the spread of an orchestra from not-quite-the-best seats. But with the advent of four channel periphery (quadraphony?) the possibility arose of presenting the listener with an illusion of sound from any direction. No longer is it necessary to fold back mentally the acoustic to surround oneself, for it will shortly be possible to simulate the effect, at least in a horizontal or vertical plane. Although we are presupposing for much of this article that four speakers are to be used symmetrically, this is not necessarily the ideal method; time will only tell.

But the quadraphonic step differs in another critical point in that for the first time the medium is ahead of the recording techniques used to feed it. It does not have the years of experimentation that benefited stereo and which made its introduction relatively free of technical and aesthetic problems. Additionally, it raised musical problems which never arose for stereo because of its stage width being coincident with that normal in the live situation.

The aim of this article is to present the different approaches possible to the medium. Perhaps it is over-idealistic to assume that we can eventually consider an ideal, even distribution of space, even on four channel tape. It is also pointless to speculate dreamily on situations which might or might not exist, technically speaking. It is necessary to think at the most of opportunities which may be exploited shortly, and for which the record companies are preparing themselves. Thus, it is wrong to assume that the shortcomings of matrix or discrete are irrelevant to a producer’s thoughts. Some facets may be objectionable, and progress will slowly be to eliminate anything that unduly limits or annoys, but to attempt to ignore them would be production suicide. Further, discrete tape is still far from being an ideal, faceless all-communicating medium as some might think. There is no such thin. All media impose their own characteristics to some extent –– there is nothing truly ‘lifelike’. Any system must define limits which must be viewed not necessarily as a confinement, but as a framework within which to work. Shortcomings can certainly be used creatively. For example, feedback was always a problem with the electric guitar, until it was exploited for its sustaining and tone-changing properties. Now, it is used as a piece of standard technique. However, with quadraphony in its infancy, the advantages are far from being fully utilized or explored, and the next few years will be spent developing within it. It is only when restrictions are felt and properly understood that they can be tackled constructively and turned upside-down. And if it took some time for stereo to reach maturity, quadraphony may take even longer.

With the stages of their development up to stereo, so-called-classical recordings were ostensibly documentary. They purported to convey the impression of the music being performed at a concert. We must reappraise our expectations of the quadraphonic medium. We anticipate that it will be capable of giving the illusion of a sound source placed at any point around us. On record, one can argue that Beethoven can be represented, as a documentary of a concert that might have happened. The record is a good attempt at recreation. The alternative is to view his music as presented on a gramophone record, and in this light the conflict between record and concert hall performance disappears. Each stands in its own right, and each takes the original score at its starting point. The record thus ceases to be a poor relation of the concert, and the concert will not be a disappointment in technical comparison with records.

In a stereo recording, any differences in recording philosophy between the two approaches are slight and are often overlooked, even if to do so is a little unwise. The stereo stage puts limits on instrumental placing similar to those experienced by the classical composers such as Haydn and Mozart, and arguments about the merit of a particular recording reflect a hypothetical concert: texture, balance, perspective and the like, as well as the directly conveyed musical aspects of phrasing, tempo, etc. With quadraphony, for the first time on record, it is feasible to present music in a radically different manner from the concert hall, and very uncomfortable it is for all concerned. Although the debates presently center on the self-explanatory ‘surround vs. ambient’ lines, the argument is really paralleled by ‘documentary vs. original recording.’ Discussing the differences is no made easier by having to use terms appropriate to the old concert hall aesthetic, but these reasonably show our dependence on past traditions.

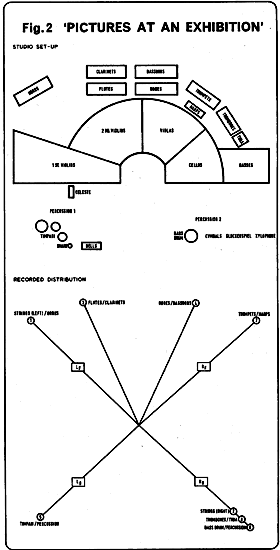

1. Left Strings/Horns

2. Right Strings

3. Flutes/Clarinets

4. Oboes/Bassoons

5. Timpani/Snare/Bells

6. Bass Drum/Cymbals/

Glockenspiel/Xylophone

7. Trumpets/Harps

8. Trombones/Tuba

The uses of the present ambient approach to quadraphony are often far from truly documentary. RCA frequently use the orchestra spread out in an arc of up to 180º. Instead of the best seat, we are now on the conductor’s rostrum, for no-one else experiences such an angle, and such a philosophy almost combines the merits of surround and ambient in providing a concert-hall ambiance with wide separation. 180º is a wide arc, perhaps three times the normal stereo listening arc. Full surround only doubles this, only doubles the space available for instrumental placing. It would seem likely that some elements would become too disparate, because of this ‘natural’ extension. And if they do, does the conductor mind as he performs? And what if he does? Our acceptance of some other ‘clarifying distortions’ is almost complete. Bornoff mentions a recollection of watching Furtwängler listening to a tape of his concert performance of Beethoven’s ninth and ‘objecting to the fact that … the repeated semi-quavers of the opening bars were to be heard separately and severally. He had intended them to be a misty, blurred background to the falling figure preparing the full statement of the first subject.’

Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste instructs that the various solo instruments be brought forward, in order to point their contrast and interplay with the body of the strings. It would be a natural extension of the score to separate these in space, for Bartók seems clearly limited by the practical demands. The Concerto for Orchestraappears not so suitable, since although the concertante element underlines the scoring, the roles of the instrumental groups change more broadly between solo and subservient throughout the piece. Yet Boulez has recorded it in surround for Columbia (CBS); while he never hesitates to innovate (obviously), in his conducting he is equally never less than consistent with the score’s demands. Clearly, the personal aesthetic is crucial, and Boulez’s own preoccupation with clarity finds an outlet here.

The Concerto was recorded in December 1972 with the New York Philharmonic in the Grand Ballroom of the Manhattan Center, and the sleeve gives extensive details of recording layout and reduction. Producer Thomas Shepard used a full 360º spread in the orchestra layout, necessitating the provision of two scores for Boulez and a considerable extra demand on his technique. Perhaps this is easy for one who has conducted two orchestras in independent tempi, but one wonders how adaptable a less experimentally-eared conductor would prove.

As explained in the sleeve-notes, in parts of the Elegia and Finale the clarinets and bassoons had their positions changed from left-back to right-back because, as already suggested, their function in the piece changes. Here, movement enabled exposure of the antiphony between clarinets/bassoons and flutes/oboes, and the step is defended in the notes which speak of ‘recording whose sole purpose is to clarify and intensify the musical experience’. That this much-trumpeted release is to be remixed before its English stereo issue (for reasons of woodwind positioning) shows that stereo compatibility, while important, is not uppermost in the producer’s mind. (In this case there was no point in insisting on an unconventional placing, even if it was as reasonable as the usual one, because it did not add anything to the music.) Eventually, compatibility considerations will fade, as they did with mono/stereo, but that can only happen if and when quad is normal for domestic listening and the disc problem has been resolved. A few years yet, perhaps.

It is no accident that the surround philosophy is strongest in America. Although we are busy celebrating 75 years of EMI and Deutsche Grammophon in contrast to the BBC’s 51st birthday, radio broadcasting of live music has a much stronger tradition here than in the US. Due to the enormously inflated costs of live as compared with needle time, concert broadcasting in the US is by now almost nonexistent. However, European radio stations have an explicit commitment to the documentary music reproduction: ‘Tonight’s concert comes to you from the Royal Festival Hall, London …’

In London the fields of broadcasting and recording overlap, so you might expect the balance to shift. The general demand of criticism here is that a concert hall balance shall be simulated, which influences the record producer in his turn. He has to sell records, and no-one will buy one with an ‘unnatural’ balance. And whatever the drawbacks of such an inherently conservative influence, it protects us from the brash vagaries of the cold commercial world outside.

EMI’s Quadraphonic remix room, Abbey Road, 1974

An objection raised to surround sound is that the listener is placed in the middle of the orchestra. To be pedantic, he isn’t, but it sounds as if he is. If you are convinced you are in the woodwind section, your belief is too far suspended. Yet it isn’t the center of an orchestra as we know it, for such rearrangement would create extreme difficulties of ensemble. You are not in the center of the orchestra, but in a place about which orchestral sounds are distributed, otherwise the flute on which you happened to be sitting would be considerably noisier than the cellos.

The balance which is attempted by the present surround protagonists is that which is obtained in the accepted best-seat-in-the-hall. This was always the composer’s intention in the concert hall (although if one accepts, as in much Baroque and earlier music, that the listener was incidental to the players, another question arises). Even this is a function of conditioning, for the cellos and basses are frequently too low, the percussion too distant; on practical recordings such difficulties are quietly remedied, without any objections. It has now reached the point where our conditioning expects a balance other than the ‘natural’ one obtaining in real performance. And in passing, it is worth noting that the experience of some producers is that the cellos and basses do not need boosting in quad remix, for their line is clarified.

The first problem encountered in spreading out an orchestra is one of texture, because an instrument is integrated within a carefully anticipated context, and because it has to relate to its musical neighbor. This is already difficult in the concert hall: a required blending of trumpet and horn is difficult because they are often so far apart. Would Bruckner have rearranged his orchestra if it had been physically possible? Conversely, when Brahms scores for cellos and basses a third apart, would the clarity given by separating slightly be an advantage? When Berlioz scores parallel thirds in flutes might he envisage parallel movements in different places, or is he thinking of a truly polyphonic flute? His characteristic scoring for unison clarinet and flute leaves little doubt that a combination of tone colors in the same place is being simulated. The fifth piece of Elliott Carter’s Eight Etudes and a Fantasy for wind quintet, is simply the same note repeated on different instruments. It is the most basic example of the Klangfarbernmelodie first introduced by Schoenberg, in which the contrast in tone-colours assumes the rôle of melody. For such a piece in isolation, one might even be tempted to pile the instruments one on top of each other, to play down their spatial differences.

This Carter example demands integration because it is specifically conceived as a melody. It would be uncomfortable to fragment any such single strand in space, and any conventional tune seems to resist any peripatetic encouragement.

But if we were to accept instrumental movement in the same way that we expect singers to move in an opera recording, then aspects of a development could be emphasized. Each voice of a Bach four-part fugue could commence at a particular point, and could move away as necessary. Eventually all would recombine. The form of the spatial orientation could reflect that of the music. To have any musical significance it must, no matter whether it is derived consciously or intuitively, and in this case it might be fair to deduce that some movement was implied by the score.

One limitation which thankfully restricts the disintegrating tendency of anything ‘surround’ is our inability to resolve directions aurally as well as we are able to visually. It is possible to sense the direction of a forward sound to within a few degrees (this even holds for loudspeaker listening, even though the sound field is not the same, and contains conflicting directional information). Fortunately, it is not so easy to distinguish the separate directions of two simultaneous sounds. In the same way, a chord is more difficult to separate and define than its constituent notes. These are basics of compositional technique – without such confusion many textural effects would be impossible. So any move toward spreading out instruments must be informed by an awareness of the composer’s intention as demonstrated in the score, and this is open to alternative interpretation, as always.

Since the producer is now in charge of a medium capable of more than mere simulation, his responsibility increases. Any creative thoughts are further complicated by the changing functions of each instrument throughout a piece, such as in Bartôk’s Concerto already mentioned. And it might feel uncomfortable to have clarinets popping up in various places, especially if they popped up somewhere to take an unassuming role – since they changed suddenly, their presence would be emphasized, with possible distortion of the music. As in present stereo opera voice production, continuity might be most easily preserved by moving instruments only when sounding.

These examples give an indication of extensions of quadraphonics which, while not on record yet, are nevertheless in many producers’ minds. But even if we subscribe to the surround philosophy in theory, the results can be very disturbing since we have many preconceived notions of the sounds we expect. The conditioning of many years is not to be denied, and even our reactions away from it must be influenced by a conscious desire to overthrow it. Nevertheless it seems essential to opt for a conservative rather than a preservative tradition. Change there must certainly be, even if its rate and direction are variable. If we were to insist on the continuance of quadraphonic records in a documentary form, we would not only be denying the right of the medium to exist for itself, but further perpetuating the disadvantages of stereo. If quadraphony is to be used to simulate ambiance, it must be justified on this basis. Possibilities for change would present themselves, and these must be judged in the context of the medium itself. It is now even more necessary to acknowledge that the recording exists in its own right. This is the same change of emphasis a happened in painting in the early part of this century when it progressed form the representational to the abstract, creating in a world completely removed from that which provided for its beginning.

In many respects the evolution of the concert hall had as one of its unattractive features the elimination of antiphonal thoughts from the minds of many composers. Such possibilities only remained within the restricted concert platform, and even such string devices conceived by Beethoven, Brahms and the German school are lost by the ‘traditional’ orchestral layout which places first and second violins together. The classic examples of antiphony come from the pre and early Baroque era: the many-choired brass of Giovanni Gabrieli, Des Prez et al, and the choral demands of Schütz in particular whose performance wishes have only recently been reincarnated by Roger Norrington’s Heinrich Schütz Choir, with concerts in appropriate settings and original choral distributions. Their Argo recording of music for two choirs is an attempt within the limitations of stereo to recreate the original intention. The sleeve recommends that if possible the listener sit between the speakers; thus, a closer approximation to the original performance is obtained.

Recording Chavez’ The Four Suns in Abbey Road, March 1972

To mention that his four-choir music is natural for surround sound is an understatement. The brass music finds an immediate outlet on CBS, and it provides them with a very convenient ‘Quadraphonic Sound Spectacular.’ For this is music that sidesteps accusations of gimmickry by neatly incorporating it into the music. However, this will certainly not always be the case, and it seems necessary to reiterate the producer’s difficulties here. The St. Matthew Passion seems destined for eventual quadraphonic presentation because of its two-choired arrangement, and because of Bach’s original intentions, which reflected his church at Leipzig (St. Thomas’). (Whether he conceived music for the particular setting, or whether his vision was forcibly accommodated, is sidestepped by acknowledging that he too was writing for a particular medium.) Whether the score suggests further changes will be seen eventually, but recording may overcome any original limitations, and it would be wrong to impose them for the sake of academic authenticity. A parallel may be drawn here with Messiah performance: many people who shake their heads sadly about large-scale productions in the Albert Hall would be disappointed by a small one. So do we ban it from the place because it wasn’t conceived there, or do we acknowledge the peculiar limitations extant? The St. John Passion seems at first sight to be fairly inappropriate for surround (and it was not designed for St. Thomas’) but conclusions must be drawn after reappraising the score in the light of quad possibilities.

Contemporary composers, in common with pop musicians, have no traditions to restrict their use of the medium, Stockhausen and Boulez between them have prompted hundreds of people to follow and rediscover the musical directionality which slumbered through the classical and Romantic periods. But again, in these examples it is necessary to be aware of what is documentary, for it will affect the way we approach it. Their music may be subject to the same debates in 150 years’ time as Beethoven’s is now.

These examples of ‘historical’ and ‘contemporary’ quadraphony provide every reason for utilizing four channels. For the demands of the medium coincide with a documentary attitude: everyone is satisfied. But it must not divert attention from the real arguments.

The larger part of this article is concerned with worrying about the implications of spreading sound around the listener, because this is a newer idea which needs placing in perspective. The prevailing contention is that the score is the starting point; concert hall and record are of the same parent. The record does not derive from the concert hall. However, in the minds of many listeners it does, and ‘the closest approach to the original sound’ is their requirement of quad. Whether this is shortsighted is beside the point, for it is a result of conditioning which is common to all of us, and if this is cut off then one would be somewhat adrift.

Again, ambient recordings can receive a justification by each of the two philosophies. The documentary one needs no further laboring. But rear ambiance can contribute very positively to forward image placement. Compare the effect of a natural (sic) recording with a crossed-pair derived reverberation or a normal commercial multi-mike recording with microphone-derived reverberation with that of an ultra-close recording utilizing added plate or small chamber resonance. Something is lacking on the latter. It has been suggested that addition of carefully controlled out-of-phase signals to rear speakers (–0²17 of the corresponding front intensity) can improve center image location, because the acoustic power and amplitude are consistent with the real situation in a way that is impossible with just two speakers. Arguments for and against pan-potting do not affect this.

Recording Chavez’ Piramide in Abbey Road, March 1972

This does not seem to have been considered for exploitation in practical four-channel recordings. But the ambiance on such as the RCA Shostakovich Symphony 15, which is an outstanding stereo recording anyway with a clear evocation of the concert hall, helps place instruments to an astonishing degree. The folding back of the acoustic, which gives a considerable amount of reverberation in stereo, opens out to an enormously spacious, faithful sound. EMI’s SQ recordings add depth, although the crosstalk between front and back speaker pairs brings the front desks more forward into the room. The disassociation of the sound from the speakers is often noted, and this shows that we have at least taken a small step in the direction of establishing a sound field rather than just suggesting one. One only becomes aware of the rear speakers when they are switched off. A backhanded compliment, but a very real one.

Until we fully understand the mechanism by which image placement is helped by the short-term room-derived reverberation, we will be unable to rationalize the effect of phase distortions introduced by matrix systems. However, the ambient productions now appearing from EMI do suggest that much information carries across. The feeling of depth seems to enhance the orchestral tone by layering it outwards from the listener in a much more real way than with stereo. Complex works such as Schmitt’s Psalm 47 for soloists, chorus and large orchestra or Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast actually open out. The CD-4 system, which does not suffer from such phase anomalies, might be a better candidate for such image enhancement, although the advantage would be a trifle academic if the ear did not require a consistent reverberation phase characteristic anyway. Since nobody relies on a coincident four-channel microphone for professional recording, it is obvious that such ambient advantages as may be possible will be reduced to start with.

A common counter-argument to ambient production points out that the listener will eventually be able to synthesize an acoustic with a fair accuracy, given the distantly foreseeable advances in integrated circuit technology. But, even sweeping technical difficulties aside, this overlooks the absence of an ideal acoustic common to all music. Reverberation time will be (is) adjustable by a single control, but such variation is crude, and misses details of room frequency response and resonance, as well as the frequency dependence of the short-and-long-tem reverberation itself. If and when the disc field settles down, we will probably see a massive reprocessing of stereo recordings for quad. These will not be as objectionable as processed mono is at the side of stereo, for components are added; there is no distortion of the original recording. The synthesized ambiance may be unrelated to the original recording room, but no more so than the artificial reverberation discreetly added to many stereo discs.

The difficulties of adapting classical music, music which we can define for our purposes as being of an age when present techniques were unknown, are traceable to an unwillingness to depart form the composer’s original concept. As such, they often parallel arguments about original vs. contemporary instruments in old music. On music written for current instruments, no problems of authenticity arise. The listener is the arbiter here, for the composer often has little compunction in altering and adapting previously finalized material to his own ends, frequently rewriting in view of subsequent developments and hearings. The philosophies and implications of the original are carried over further. Maxwell Davies’ preoccupation with and exploitation of the tensions between transformed and original are well known. But it was Stockhausen who crystallized the idea of a dynamic tradition in Kurzwellen mit Beethoven (Stockhoven–Beethausen Opus 1970), which was prompted by a request in 1970 for a lecture on Beethoven. Four players are each equipped with tape recorder and loudspeaker by which they can play a continuous but disjointed stream of Beethoven’s music. They proceed to react against one another and play their tapes as and when it feels appropriate.

In Stockhausen’s words, ‘our aim is not to “interpret”, but … to hear with fresh ears musical material that is familiar, “old”, performed; and to penetrate and transform it with a contemporary musical consciousness. For this music is not fenced off and dead, but is rather a living generative force: an immediate cause and pretext for the new and the unknown.’ The heard results are important as a demonstration of the underlying idea. If the adaptation and extension of classical music to the gramophone is less extreme, it still requires the same reappraisal.

Classical music production is easier to rationalize than pop. Classical music can be described in terms of a set of established values, even if the contemporary preoccupation is in denying them. The other cannot. Where pop music has a tradition, it is not codified, and attempts to do so in print easily sound pretentious. The end results sound dramatically different, and are enjoyed in different fashion, for better or worse. And yet pop production seems to respect the same values as classical, with a different emphasis. Where it differs is that it is completely unequivocal in its wholehearted use and abuse of the gramophone facilities, and as a result it does not suffer from the curious schizophrenia induced by the rigors of having to serve a performing culture. It couldn’t anyway, for performance sound is often dire. Perhaps the sound of Blind Lemon Jefferson might have been reproduced compete with his chickens, but this would be as silly as the example of recording the Trout Quintet in a room full of stuffed furniture, quoted by Paul Myers of CBS in his original argument for surround sound. With such freedom, you would expect progress.

For pop, it is only what it sounds like on the record that counts, and a novelty or new direction is as attractive as it is abhorrent to a classical tradition. And from the earliest records, when players stepped up o the microphone for their solos, no-one has accused the gramophone of purveying reality. The record dominance is so all-embracing that PA in performance will consciously set out to simulate a recording, replete with stereo panning and modest effects. This is even carried to the extent of people using prerecorded effects tape, or that an ambitious drum PA sound resembles the record more than the real thing.

In the classical field it has only recently happened that new techniques have been exploited for their inherent possibilities. Previously, successive technical refinements were in terms of a progressive approach to perfection, and production did not utilize a new invention unless it moved the recording closer to a preconceived ideal. Pop music uses something if it sounds interesting, and it does not necessarily have to be of a high technical standard. For example, the modest Grampian spring reverberation unit is frequently used in the studio, not because it sounds like the real thing, but because its peaky response enhances instruments such as guitar and flute. An equal signal to the front speakers out of phase produces the well-known disturbing imprecise effect; this was gleefully seized on by George Martin in producing Sergeant Pepper. Since there is no predetermined standard, anything is fair game. And there are none of the precedents that form a line which can be extrapolated forward in classical music. There are relatively few consistencies, but many innovations in pop. Everything derives from the techniques available, and the best one can envisage at present is a gradual extension and inspired variation of stereo methods. So a brief general mention of current studio techniques will give the clearest insight. Here, the limitations of the reproductions also make themselves felt.

Any self-respecting rock band records masters in at least 8-track, and has done so for the last four or five years. 16-track tends to be used whenever possible, although this is often just for the convenience of musical subdivision, and 24-track (on 2 in. tape) is now being successfully introduced into some London and American studios. Such extensive division means that original multitrack recording techniques for stereo are at present practically unchanged when quadraphony is in mind, although readjustment must follow. Further, it means that old masters can be remixed to four channels; at the time of writing, Tony Clarke and engineer Derek Varnals have remixed all of the Moody Blues’ seven albums (except In Search of the Lost Chord, which is to be finished shortly). Although at first Days of Future Past was only recorded in four-track, it was still feasible to remix it for quad.

As regards separation in pop recording, there is no difference of approach if quad is the intention. The extreme separation automatically sacrifices any ‘natural’ sense of context in the interests of artistic flexibility, and the decision is not affected by the end product. Some leakage might actually prove beneficial, as it can in stereo, but it is not sought after and is generally regarded as a nuisance. By the same token, monitoring is unchanged, since the aim is to get the music recorded for eventual remix, although of course the engineer is far from being unconcerned with the balance and blend at this stage.

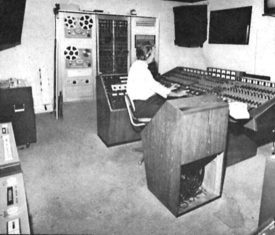

Monitoring for remix gives difficulty. The automatic tendency is to put the speakers in the four corners of a square room, with resulting detriment to the smoothness of the bass response because of the irregular horn effect of the corners. EMI, in their specially-designed quadraphonic remix room, alleviate the problem to some extent by mounting their JBL Monitors high on brackets rather than having them floorstanding, but the corner still provides emphasis. The obvious solution is to mount one speaker in the center of each wall, with the engineer oriented to face a corner of the room. (This, again, is merely thinking in terms of symmetrical placement.) However, we live in a practical world, and until triangular mixers start to be the thing, speakers will remain in corners. Other studios often have markedly rectangular control rooms, so that speakers face each other across the room. Lack of symmetry to match the speaker is not consistent in all directions, but this is not troublesome in practice.

It is at remix stage that the limitations of the disc reproduction systems being to bite. But the restrictions must be viewed in a more constructive light than is often the case. The normal tendency is to point out what a system cannot do, and her it is inevitable because the standard is set by the four-track half-inch tape master. However, it is a cold fact of life that at present there is no disc system which will reproduce four channel tape with the efficiency with which it can cope with stereo, and we already concede a live with the stereo cutting restrictions. It appears that this will be so until some Technical Revolution arrives. The obvious candidate is some form of FM disc for which audio would be indebted to video technology. Not only is the bandwidth available, but the familiar deficiencies of the analogue disc, surface noise and end-of-side distortion, do not appear. Unfortunately, since audio industry Technological Revolutions seem to happen but once every ten years, we may have to wait a while. The most we can see at present is a combination of matrix and CD-4 disc, as has been proposed but not much exploited on record. Although much of this article has concerned itself with possibilities of discrete channel reproduction, present activities must be viewed realistically, and acceptance or rejection of the medium based on the whole.

EMI’s Quadraphonic remix room, Abbey Road, with Stuart Eltham engineering

The Moody Blues’ remixing, which was done in response to a request from the Amp Corporation of the USA, was intended for discrete tape in cartridge form. No disc version is intended at present. (Incidentally, it is an interesting paradox that the quad cartridge market in the States relies almost completely on in-car entertainment sales, so we have the prospect of an environment relatively hostile to audio keeping afloat its furthest technical advance; and not only that giving possibly the best commercial results.) The Moodies have always been outstandingly produced, and they will doubtless be among the leaders in exploiting quad. The textural problems mentioned earlier could have proved troublesome; their stereo is notable for its thick layering, and the remix has thinned it somewhat, but the dramatic advantage of the placing more than compensates.The earliest albums were recorded in two successive four-track stages, and their rejuvenation was an interesting exercise. One four-track tape was filed, then submixed to two tracks of another four, from which the original stereo master was produced. Six tracks are thus made available by rerunning the two original four-track masters in sync. But this still did not give sufficient flexibility, particularly for the orchestra, which was originally recorded in straight stereo on two tracks. In passages where the orchestra is unaccompanied, the effect would be anticlimactic after the full orchestra-and-group surround if it were merely placed across the front speakers and echoed in the rear.

After some experimentation, the orchestra was placed in front, with ordinary reverberation from the rear, but additional plates were used with deliberate peaks and dips introduced into the response. The orchestra at the front was treated in reverse of the echo: peak for dip and dip for peak. Although ordinary top and bottom roll off/on was considered, it was rejected as giving too lopsided an effect. The final result displays an astonishing amount of spread and movement, particularly on transients and high notes such as from harp and flute. Further, there is no aurally obvious phase anomaly, as often proves objectionable with reprocessed mono, or pseudo-stereo. If there is any discrepancy, it is between front and back and therefore masked by the limits of side-hearing perception. Although the plate-echo process relies on phase distortion, its randomness as used in this synthesis is in marked contrast with more controlled forms. And it was only conceivable because there were no ideals to influence the end product other than basic musical ones.

The Moody Blues’ quad remixing was done specifically for four-channel tape cartridge, with minimal restriction on instrumental placing. Remixing for SQ is more complex, and the engineer has an already problematic task complicated still further by limitations on his instrument placement. The disappearance of centre-back images when reduced to mono is well-known, but cutting difficulties restricting out-of-phase (vertical) amplitude mean that such sounds could not be cut at a high level anyway. In practice, the line from centre-back to mid-centre is avoided in balancing, and this reduces the scope of any ideas of so-called ‘in-head’ sounds, sounds which by being placed in the center of the room literally feel in one’s head. However, developments are in progress which will permit this in the near future. The normal place to put the bass guitar in a stereo recording is in the center, which does not trouble the cutter at all, in sharp contrast to the situation if strong signals were put to the left and right.

The corners give strong location, and are used freely, although the tendency seems to be to keep the heavier instruments forward. Since centre-front is natural for the bass, the drums often follow it to settle into a conventional stereo position. However, centre-sides are also difficult for precise image placement, although this could be turned to advantage if a diffuse sound were the requirement: inherent phase anomalies are assisted and masked by the ear’s inability to resolve side sounds. However, centre-side level is also slightly limited by the cutting, so if a thick, heavy bass is wanted, it cannot comfortably be put there.

A standard technique for spreading the bass across front stereo is to use two feeds, one directly injected from the instrument, the other from a microphone on the cabinet. If the phase were consistent between the two, the perceived image would be central; that it usually isn’t indicates the discrepancy, and stereo cutting can prove troublesome. Extension of this technique to the disc quad is unlikely. Fast tape delays give a similar effect, by acting as a frequency-independent delay line, but the same difficulties recur. In short, standard image-broadening techniques cannot be comfortably applied to disc; they are often uncuttable due to banning of large difference signals at center side and center back, and strong signals in the areas of vague definition – both are effectively the same, of course. It is paradoxical that we should be thinking of spreading the image, anyway.

It is possible that matrix limitations will be exploited just as out-of-phase stereo has been, although the aural effects are not on tape but would be anticipated on encoding. However, current developments in logic circuitry, with all their own peccadilloes, are certain only in that they will eventually supersede today’s simple black boxes. So with many matrix systems available (albeit little on record apart from SQ) one wouldn’t want to labor on this point.

The CD-4 system also falls short of many expectations, although some are being resolved. Predistortion techniques are assisting carrier linearity, and it is hoped that present restrictions in cutting amplitude will lift to give playing time comparable with stereo. Noise and tracking difficulties are being reduced, and real-time cutting is foreseeable. The system, as always, is a compromise of conflicting interests, many of which are traceable to the channel interdependence of the disc. Again, this limitation is simply an extension of stereo, and such restrictions inevitably apply to all disc systems. The conflicting requirements of bandwidth and amplitude within a fixed information storage capacity will continue to be a general principle applying to all reproduction systems, tape as well as disc. How they are optimized depends in the first instance on the music to be reproduced, but producers will certainly adjust within its limitations (assuming that they persist and that the Technological Revolution does not overtake us before they do so).

If stereo can often seem empty, surround can be positively barren. The difficulty stems partly from the use of carefully separated tracks. In conventional ultra-close microphone technique, the ambiance of the studio is practically denied, and the existence of any useful short-term ambient information is accidental. The aim is to simulate the sound field, not reproduce it. Long-term ambiance comes from echo plate or chamber, but since in general there are fewer echo-send channels than instruments, this does not aid directionality, but merely clothes the overall sound in response to the common input. Experiments with quadraphonic plates have not been too successful so far, and have not spawned any high quality commercial versions. Present practice is to use two stereo ones. Echo chambers have always provided a smoother, more acceptable sound, but their size seems to preclude much use other than in the wide open spaces of North America.

Recording Chavez’ Piramide in Abbey Road, March 1972. London Symphony Orchestra conducted by the composer. Producer: Paul Myers. Engineer: Robert Gooch

This separation has the subjective effect of denying the instruments a common context, and hence the sparseness mentioned earlier. For example, in stereo drum recording, the kit can often seem over-separated, particularly if one part is used sparingly and the producer has spread the others out unduly: if he hits his floor tom-tom only occasionally and it is too separate, it can seem like an irrelevant bonking, unrelated to any of the other sounds. Thus, quadraphonics makes the drummer nervous. On the other hand, bringing a stereo drum kit forward so that the bass drum is hitting the top of your head is startlingly effective, if rather oppressive. It increases the immediacy without any extra disparity between sections. For the solo instruments, the difficulty is that they can find themselves isolated in one place. Since the image width is marginal in comparison with a classical string or wind section, and since there isn’t a common relative ambiance, it is difficult to get the sense of coherence of a mono single. Maybe Phil Spector was right.

It is probably worth looking at an example which goes wrong. The music of Sly and the Family Stone relies for its rhythmic power not so much on the individual instruments but on their interaction. Independent activities are quite banal if singled out, but coalesce to form an exciting rhythmic texture which fills a stereo spread fairly comfortably. But when this is pulled out in quad, a sense of interrelationship is lost. In Dance to the Music at one point there is a gradual accumulation of solo instruments (‘I want to add a little guitar …’) which bit by bit enlarges the song by adding to what went before, extending rather than breaking away. Whereas on the stereo mix all is confined between the front speakers, in quad things disintegrate when instruments are dumped in the four corners. The American Gamble-Huff combination is now reproducing for quad, and on the strength of 360 Degrees of Billy Paulseem destined for as much success as in mono and stereo. Their production is characterized by clean, open arrangements where everything is meant to be heard. The extension of this album at least shows that such an approach transposes very easily, in direct contrast with Sly Stone.

Although no conscious enlargement is taking place yet, it appears that when original recordings are made specifically for quad, more filling-in will be needed, and this might be one eventual justification for 24- or 32-track recorders. Objections to the cost of such a production mirror those of a few years ago about 16-track for stereo. Whether we re now at the ceiling remains to be seen.

Whereas Sly uses quad to apply gimmicks to the music, other more successful productions reverse this. The Pink Floyd, also among the leaders in production techniques, no use quadraphonic sound in performance, albeit in a very different way to on record; all three albums since Atom Heart Mother have been remixed, although that is the only one presently available on disc. The most recent, Dark Side of the Moon was remixed by Alan Parsons, the engineer, with the intention of maintaining the stereo balance while exploiting the four-channel medium subject to the limits of the SQ disc. The stereo version is characterized by a thickness of sound which is nevertheless localized– in contrast with the Moody Blues’ approach – and it extends to quad without much difficulty. But when they attack from all sides with the alarming and chiming clocks at the beginning of Time, or when the rhythmically tape-delayed vocal line in Us And Them follows from all four speakers in turn, their point is made rather more easily. Unfortunately, already the routing complexities are mounting up. This particular tape delay needed to pass through two record-replay stages before insertion, in order to synchronize with the music. Although stereo mixing moved successive image positions, such luxury became almost necessity in quad; an 8-track machine was needed for just this one effect. If Alan’s Psychedelic Breakfast, the sound-effects extravaganza on Atom Heart Mother, doesn’t make full use of extension to quad, it is a reflection of such limitations.

Classical recording, which has now embraced 8-track, and occasionally 16-track, is also amenable to quad remixing for ‘surround’ or ‘ambient’, especially if derived from close microphone techniques. Although pure unadulterated coincident pairs are used commercially on rare occasions, there do not seem to be any records around at the moment using its quad equivalent. This seems a reflection of the large forces on current issues, which are mostly orchestral, and the considerably increased difficulty of achieving a satisfactory natural balance within a room too small for them. However, given suitable balance, ambiance and patience, coincident technique is perfectly feasible, although any surround effects must obviously happen in the room to be recorded, with subsequent playing difficulties. This technique, however, will only serve the documentary philosophy. In the experience of CBS, it is not always necessary to tamper unduly with the orchestral studio setup for surround. Although their much publicized Abbey Road recording of the Rite of Spring with Bernstein and the London Symphony Orchestra used an orchestra scattered around the studio, producer Paul Myers has since used a fairly conventional arrangement. Fig. 1 shows the layout he and EMI engineer Robert Gooch adapted for their recent Chavez recordings, again in Abbey road, which involved a large orchestra with extensive percussion. There was roughly the same number of microphones as for stereo, and the division of the eight tape tracks was also similar, as shown in the diagram.

Seymour Solomon, of Vanguard Records, USA, is now something of a father-figure among quad producers. For July 1973 sessions in London, he used a particularly elegant setup to record Pictures at an Exhibition, and this is shown in fig. 2. There were no screens employed at all, and it was because of his rationalization that these objectionable necessities became superfluous. The intended quadraphonic remix is also shown. For example, consider the trumpets which are certain to bleed into the microphone covering the violas to some extent. If the remix puts the trumpets and violas at opposite sides of the room, the effect would be intolerable, but because it is arranged here such that the brass is located near the appropriate string sections, the overall effect will be to broaden out the brass sound without confusing it. Because of the systematic way in which he folds out the orchestra, this holds whichever potentially troublesome section you consider -– and the whole reduces to conventional stereo when folded forward. His philosophy differs slightly from the present CBS surround approach in taking the orchestral layout as a more emphatic starting point, although problems of separation and interrelation are frequently solved by the best orchestrators. Since they were working with that problem initially, such opening out is almost a simple extension. Ravel’s arrangement often seemed to open out in an unforeseen, logical way as a result.

Traditionally, opera has been the first musical form to benefit from improved techniques in recording, possibly because of its combination of conveniently short, assimilable sections with its relative inaccessibility of performance. Opera tends to be expensive and to be produced in less-than-ideal acoustics; thus it benefits immediately from recording. However, the record is blind, so one now accepts that the lost dramatic visual element must be counterbalanced in sound’s own terms. This is a battle that is not yet properly won for concert hall music, even if the principle is discreetly applied in recording. With opera production, we are now accustomed to having the soloists out forward in front of the orchestra. And we happily tolerate soloists crossing the stage in a relatively short space of time -– they can run the width of the orchestra remarkably quickly for their age and size. Disbelief is well suspended, and we should be thankful. And we can sink Bayreuth orchestra pits at the push of a fader.

Yet so far, no-one has issued a quadraphonic opera, and the repertoire has been singularly neglected by the various companies active in the field. It becomes more surprising when one remembers that many operas are recorded 8-track, often 16-track, so that the elements are all comparatively separated as a matter of course for conventional stereo reproduction.

Expense aside, a ready explanation for some might be the sheer scope of the medium in its application. The constituents of symphonic music relate contentedly to each other in the concert hall, and rationale is fairly clear. But opera adds to orchestral difficulties those of chorus, soloists and their movement. And so far we have avoided the vexed question of sound effects. Stereo is quite content in its altering of perspectives and positions for dramatic effect -– but such production takes time and money. If they come off, these ambitious touches are generally noted and applauded. But if not, if one element is out of balance, it destroys everything, and the result can be decidedly worse than straight presentation. Let us not talk glibly about sound effects as if they were just thought into existence.

Apart from such mechanics, there is the problem of choosing the listener’s seat to full advantage. Some would put him in the prompt box, with orchestra and stage occupying back and front half-circles. (Or we may put the listener on the ceiling with the speakers on the floor ….) Or the orchestra could be in front and dispersed around is present 60° or so, with the whole perimeter of the listening area treated as the stage. This would increase the producer’s ‘stage management’ problems, for it would take longer to walk around you than it would to pass in front. Suggestions of moving the orchestra might find outlet here, although for many people the thought of instrumentalists wandering around would be a little too much even if one were dreaming of being in among the action. But are we going to continue with a static magic flute if we have the means to move it? At the least, it should follow Tamino. Further extensions of this argument in less obvious situations are easy to anticipate.

Here, as ever, each piece must be tackled on its own terms. Wagner’s voice treatment would not be too amenable to separation from the orchestra, since the two tend to form an integral part, a composite texture. This might generally preclude use of a surround-stage. But in an aria from Rossini or early Verdi, separation might be better, since the orchestral tutti is used merely as an anchoring point for the vocal line, merely as a backcloth. But its banality could be cruelly exposed. Here gain, the producer is thrust into a position of responsibility in deciding on the significance of the various dramatic possibilities, much more so than in stereo. With Britten, a ‘phone call will do, but Mozart is not so accommodating.

Pierre Boulez and the New York Philharmonic recording Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra in the Manhattan Center, New York, 18th December 1972

When quadraphonic opera arrives, it will have to be in grand style. For the first time, some of Wagner’s stage management directions can be implemented -– his ideas were often hopeful rather than practical. Directions for surround effects abound, such as the cow horns in Act Two of Götterdämerung answering Hagan ‘from various directions’, or the similar scene with the Landgraf at the end of Act One of Tannhäuser. And for once thunder might be on top of us, although to be similarly involved with the fall of Gibich’s hall might prove a little traumatic. However, one will probably still feel limited by the absence of height, for Wagner’s directions draw as much on heights and depths as do his themes. Brangäne’s calls from the ‘high watchtower’ above the lovers Tristan und Isolde will be simulated above quad in the same way as horizontal position is implied now; but with so many effects like this required, it may prove more feasible to wait for octaphony or whatever. Orchestral extensions will come, for the Ride of the Valkyries is very much an aerial experience – but one would expect producers to tread carefully.

The Verdi Requiem, already recorded by CBS with rear ambiance, would lend itself naturally to broad changes of scenario, since its inclination switches from dramatic to theatrical to personal. Again, however, the producer would approach warily. But this particular mass has the same staging limitations as opera, and its treatment must reflect the theater as the church. Rather more hesitation would occur before any tampering with a Missa Solemnis.

A similar replacement of vision occurs in a ballet score. The classic example is the Daphnis and Chloë Suite No. 2 by Ravel, in which the flute personifies the dancer, or Bartok’s Miraculous Mandarin in which the clarinet plays a similar role. To move the instrumental sound in sympathy with the music would either enhance the scoring or it would say the same thing twice and therefore prove superfluous. If an intuitive correlation were to evolve between the dynamics and phrasing of music, and position, one could not be a mere reflection of the other, or it would only pad. But the spatial form must derive from the music, and be seen to relate to it in a way neither too obscure nor too obvious. We already acknowledge simple possibilities, but it may be that, given the stimulus of an increasingly more open concert situation, the future listener will be much more aware or spatial implications and interrelationships than we are. And the evolution of a reproduction system capable of precise image placement will assist further.

In a sense, the composer now becomes his own choreographer. The sound is now the dancer. The directions for image movement in Bernstein’s Mass, for example the oboe solo Epiphany which skips from speaker to speaker, seem conceived in recorded terms. Use of quadraphonic tape in performance transposes naturally on to record, one of the few pieces to do so successfully, although this is largely due to the tape’s being a record of ‘natural’ sounds as opposed to electronic. With traditional scores, we are on even trickier ground than with Bach. There will probably be some very trite ‘dancing’ once experiments are under way but, as with simpler aspects of quad now, techniques will evolve by trial and error rather than through isolated academic deliberation. But who would approach the Rite of Spring with impunity? Boulez’ recording of the Miraculous Mandarin was recorded with rear ambiance only. Judging by his Concerto for Orchestra recording already mentioned, his return to this score could be illuminating.

So far, electronic music has been avoided. However, it shows every sign of becoming a popular force, due to the emergence of a generation which has few preconceptions about music and the increase of pop borrowings, a process which works both ways. It is a strange coincidence that this is a generation that hears its first music from a loudspeaker. Media confusion sets in with a vengeance here. The best-known works – for example those of Stockhausen, which are widely available in remixes for two-channel disc – were often not conceived with the listener’s front room acoustics in mind. Nevertheless, one eagerly anticipates four-channel issue of Gesang der Jünglinge (for five loudspeaker channels) or Hymnen. Stockhausen, incidentally, in a note on the work reflects the Messiah performance aesthetics when he speaks of ‘Hymnen for four loudspeakers and soloists: Hymnen for radio, television, opera, ballet, concert hall, church, open air.’ In composing in a fashion accommodating different settings he acknowledges that no one is ideal, and takes steps to permit adjustment. To realize the conception fully, an intermediary acoustic must be interposed; that this is often unsatisfactory is shown by some disastrous attempts by record producers of the past to marry electronic and live sounds, a problem that is shared with the performers. Simple sounds, such as that of the ondes martenot and its appearance in Messaien’s and Varèse’s music do not really concern us, for they are treated easily as conventional instruments (Jolivet even wrote a concerto for the ondes). But when complex noises are attempted, confusion often occurs – the ear does not know how to interpret.

Quadraphonic electronics in the concert hall are exploited by few -– Stockhausen apart. That the retiring Milton Babbitt is one of the leading exponents (in an occasional way, as with Philomel, for soprano and tape) speaks for itself. The few extensions beyond such four-channel techniques are practically inconceivable on disc. Consider (briefly) the realization of Varèse’s Poème Electronique, created for the Philips Pavillion at the Brussels Exposition of 1957. For this, 3-channel tape source was used in conjunction with multichannel control tape and 425 loudspeakers. When that experience arrives in the living room, things will not be quite the same again.

The real advantages to be gained are in the home. For once, this is no intermediary’ there is never any question that we must be tricked into believing that the medium isn’t there -– disbelief does not enter into it. In this way the extremes of the record/concert-hall polarity are pushed out, and one wonders whether Morton Subotnick is prophetic when he suggests ‘that there should be more emphasis on works of art specifically for the record medium and less emphasis on recorded performances…and when there are recorded performances they ought to be just that … a recording of a performance … no editing … no fancy recording techniques … so that the emphasis on works intended for live performance keeps the emphasis on the “live” part of it’.

The first commissioned work specifically for the gramophone record was only realized as late as 1967. Subotnick’s Silver Apples of the Moon was instigated by Nonesuch and made extensive use of the limited stereo spatial effects possible. Later productions for American Columbia (CBS in this country), Touch and Sidewinder, exploited four-channel techniques fully, assisted by techniques permitting panning to be voltage-controlled. The similarity between space and other compositional elements become even more obvious when position can be controlled in the same fashion as pitch or dynamic. In these later works he refines the material, making the sounds shorter and sharper, possibly because such sound is easier to place. (For a similar reason, Harry Partch’s multi-layered percussive music is a natural for quadraphony. That CBS think so too shows in their making it available on quad import but not issuing it here in stereo.)

Walter Carlos’ realizations of Bach result from his subscribing to the dynamic tradition mentioned earlier. Many of his detractors have a more preservationist approach and disagree accordingly. He raises the possibility of extending Bach’s music to include the spatial freedom denied him. It would be interesting to separate a four-part fugue and allow the lines to run and move in space, so that their positions are defined by the music and by their interrelationship with other voices. To do this thoroughly, to consider the position of each note as closely as its dynamic or duration, is a huge task and the studio difficulties are prohibitive. Splicing would be increased, and the prospect of a producer snipping way as frequently as the composer in a ‘classical’ (tape, not voltage-controlled) electronic studio is not an attractive one. Glenn Gould, whose complete commitment to the gramophone is well-known, is presently experimenting with the music of Scriabin among others, and by setting different parts in different acoustics, for example, he hopes to expose the structure more clearly. Doing this for established pieces using space separation is a natural progression, but a well-written piece may not need it. This begs the question of how one would tackle a Boulez piano sonata, whose complexity is justified by a strong but often invisible internal logic.

There are no conclusions to be drawn coldly on the basis of any of these arguments. It would be pointless to try to make them – they will only evolve in practice, to be rationalized later. But it is only possible to promote any case if one accepts classic counterarguments as Benjamin Britten’s famous speech will cease to have any relevance, because it will at last have risen above being a simple music substitute.

Reactions can only reflect personality, and in matters of taste it is impossible to generalize. Exposure to surround sound (pop as well as classical) provokes responses varying from wild enthusiasm to a strong desire to leave the room. There are few things which generate such extreme polarities, and no-one remains indifferent. But quadraphony exposes so many misconceptions and demands the discarding of so many tenets. Above all, we must not fabricate rules, but allow space for development. Busoni’s comments, first published in 1911, with regard to a new music aesthetic, still apply:

‘Music as an art, our so-called occidental music, is hardly 400 years old; its state is one of development beyond present conception, and we – we talk of “classics” and “hallowed traditions”! And we have talked of them for a long time! (Tradition is a plaster mask taken from life which, in the course of many years, and after passing through the hands of innumerable artisans, leaves its resemblance to the original largely a matter of imagination.) We have formulated rules, stated principles, laid down laws; – we apply laws made for maturity to a child that knows nothing of responsibility!’