Music Distribution

We are currently experiencing some short-term hiccups with our physical CD distribution: in the meantime please click on the album links on our Albums page and hit the Amazon buying links to check if your title is available .

Download sales continue to be available via the usual services and you can also still stream our music as usual.

Music Distribution

We are currently experiencing some short-term hiccups with our physical CD distribution: in the meantime please click on the album links on our Albums page and hit the Amazon buying links to check if your title is available .

Download sales continue to be available via the usual services and you can also still stream our music as usual.

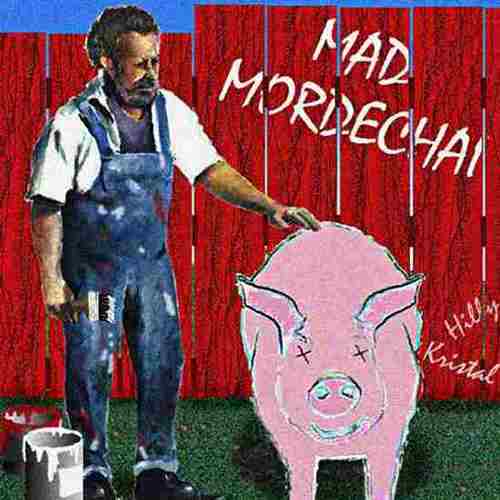

CBGB Past, Present And Future

Hilly Kristal has been managing downtown music clubs since the late ’50s, beginning at The Village Vanguard, then with his own club, Hilly’s on Ninth Street in the late ’60s, and finally at Hilly’s on the Bowery, later renamed CBGB.

With Ron Delsener, Kristal began the popular Rheingold-Schaeffer concert festival in Central Park. At CBGB, Kristal was at the center of a seminal New York music scene which launched the careers of such influential artists as Patti Smith, Talking Heads, Blondie and The Ramones.

In the following interview, conducted over sushi and beer at CBGB, Kristal discusses the New York club scene, the politics of records and radio, his new tape and record label, what it takes to make it in the world of rock, and the meaning of OMFUG.

Q: Name Two Enemies Currently Of An Evolving Creative Music?

A: Top 40 Radio And Lazy Musicians.

Marc Berger: New York City has produced several local music scenes that ultimately went on to have international significance – Folk City in the early ’60s, Max’s Kansas City in the early ’70s, CBGB in the mid-to-late ’70s. Is there a local music scene in New York today?

Hilly Kristal: Well, no. I’d say not. It depends on what your definition of a scene is. CBGB stands for ‘Country Bluegrass Bar’ which is what I intended to do when I started this place. But at the time there was no ‘scene’ and all these people had no place to do their own rock. There was no scene. No nothing. No place where a person could play their own music at all in New York. You couldn’t do it.

What year was that?

’74. ’75. You had the Mercer Arts thing, which was doing some things sporadically. Max’s was changing hands and closed up just before I opened and then reopened several months later. They were doing the older thing Max’s had done.

Mickey Ruskin had started it as a chick peas and steak place and all that stuff catering to artists. When it started it was a restaurant but it was like a hangout for everything. And then it was mostly writers, artists, photographers and he and another guy had the Ninth Circle and Max’s grew into a music scene when he opened up the upstairs, doing kind of a folky thing.

But, when I started, there was nothing else happening. There was always a place here and there doing things two or three times a week or closing and opening. And when I started doing it steadily I said the only way they could play here was to do their own music.

Not that they can do it. They had to do it. Then all these bands started to flock here. That’s when it started to become a scene because it was the only place where creative musicians, or so-called creative musicians, could come and do what they wanted to do as a means of self-expression.

It’s hard to believe there was no other place in New York City where you could do that.

No place else in the country from what I understand. It was then a very disco-ish period.

Disco and Springsteen.

Springsteen was not yet an influence, though I guess he could do more of his own thing than others down in Asbury Park, because he was a local. I mean who’s local in New York. I’m sure a local band could do dances, I don’t know, at The Firehouse or something, and play some of their own music mixed with pop tunes that were happening. But as far as doing anything musically where you could grow as an artist, it just didn’t happen. Not in rock during that period of time. It was very difficult to start. There was a pop-disco market and a hard rock market and that was the only way that people who operated a facility could make money.

By having things that were not new and creative. So when this started it took hold because, look, you had The Soho News, The Voice, The Aquarian, Rockwell at The Times, and what else were they going to write about?

You’re saying it kind of went hand-in-hand with a thriving local music press?

Even national. Rolling Stone. Melody Maker. When I had this festival for the Top 40 unrecorded rock bands in ’75 Rolling Stone sent people from San Francisco, Melody Makersent people. You know, New York is it. The Soho News was pushing The Village Voice. Rockwell came down all the time. He used to write. You had all these writes who were very aggressive into music.

And how is today different?

Well, I’m saying, why was this a scene? There was a scene between Max’s and here once Max’s reopened. It was small but it spread around the world. It started here.

Then there was no scene in London. Nothing happening. There was no punk. There were bar bands but no scene. Nobody wrote about anything. But it kind of started here. When the clubs and bands there saw the Ramones and this band and that band happening and saw that they could get signed and, you know, receive adulation, they said ‘Why can’t we do it?’

So all of a sudden Melody Maker and NME – I don’t know if Sounds was quite around then. But they started writing about their own things and of course there was much more need there than here because there it was not only a means of expression of your psyche, but I mean there, in U.K., young people had no place to go.

That’s why the punk thing started. Mainly there. I mean everybody thinks that this is probably a punk club. But this was just a catalyst for everybody recognizing that there was much more going on among the punks in U.K. than here. Here there was just a variety of people wanting to do their own thing.

When I started, The N.Y. Dolls were the main thing so you had the glitter era kind of coming to an end because The N.Y. Dolls never made it big. There were a lot of people into a lot of kinds of music but it was mostly just self-expression. I mean Patti Smith, a lot of people kind of think of her as punk but to me she’s not punk. She was a poet.

Talking Heads. I don’t think were punk. Ramones were punk, a few others were. But most of them were different forms of rock and hard rock and garage type things. And some had a little more fold elements. Some crossed over a little bit into jazz.

There was, I think, a movement to being more fundamental in their playing. To lessen all the guitar frills and be more basic. Playing basic chords, basic structure and having something more to say. There was a new wave, if you wanted to say new wave, of music. But it was really based, I mean these were not musicians, these were people who wanted to say something and picked up instruments to have their say.

Couldn’t you say the same thing about the scene in the early ’60s that developed around Folk City and Bleecker and Third Street?

That scene really started back in the ’50s. I was part of that scene. I sang folk music at the Café Wha. But that was a folk scene.

But weren’t they also people who were not primarily musicians, but who, as you said, picked up instruments to have their say?

Sure they were. But that was folk music, and it became the music of the country for a while.

To what extent do club owners and their feeling for the music contribute to making a scene happen?

Well, there are a lot of things that are wrong. I mean I think I’m lucky in a way. Take Folk City. I mean they re-established and then were moved out by high rents. In  the ’60s and the ’70s rents were low. Now, a place this size, I mean two years ago my rent more than tripled. If I had to start with anew place and my rent more than tripled that would be tough. At least I had a name that was established. But for somebody else starting in the last two years ·

the ’60s and the ’70s rents were low. Now, a place this size, I mean two years ago my rent more than tripled. If I had to start with anew place and my rent more than tripled that would be tough. At least I had a name that was established. But for somebody else starting in the last two years ·

Back in ’80, ’81, ’82 there were 20-25 clubs doing rock. And I don’t think there was a scene then. I think it was a bad scene. It was spread all over creation. Most of the people got bored, sick with it. Most of the sound systems were terrible. It got into a conglomeration of a lot of pretty bad places to hear music.

In ’78, ’79 there was The Mudd Club, and here, and Hurrah’s and then all of a sudden it went from about five clubs to about 20-25 clubs and that’s when it got bad as far as I was concerned.

There were always others opening and closing. But they were closing because it doesn’t pay to stay open. There was neighborhood pressure. I mean there’s no sense fighting it if you can’t make any money.

I understand that you were involved with club management long before CBGB. Did you grow up in New York?

No. I was born and raised on a farm in Central Jersey, and I was a musician. I studied violin, voice, I studied opera, sang, played and concertized. Then I got into folk music and sang in the glee club and then sang at Radio City with all the Rockettes around and ballet dancers.

Is that for the record?

Sure. Why not? I did solos. I always wanted to be in music.

I grew up thinking I was going to be a concert violinist. But then between working hard on the farm I became disillusioned and took up singing and kind of backed into folk music.

When?

When I got out of the Marine Corps I was singing at Radio City and then would go downtown and sing at Café Bazaar and Café Wha and a couple of other places is ’56 and ’57.

Were you singing songs that you wrote?

Yeah. I’d write and sing. I’d go down there after getting through at Radio City. Those were fun years. The ‘beatnik’ era, which went into the ’60s, and we know what era that was, which then went into the punks.

There was a big gap there.

Where? Between ·

Well, between the hippies and the punks. There’s an enormous black hole there. About three years of nothingness following Watergate and before punk arrived. During that period it seemed the emptiness-disco thing happened as a response to the disillusionment of Watergate. Dark Ages.

That’s true. There were about two or three years where nothing was happening. That’s why there was a need for this place, for self-expression in music.

What were you doing in the middle to late ’60s?

I managed the Village Vanguard from ’59 through ’64 and sang at Radio City off and on. Then I started producing the Ford Caravan of Music. It was a college concert tour sponsored by Ford when the Mustangs came out initiated by Iacocca.

It was primarily folk and jazz artists like Nina Simone, Roger Miller, Herbie Mann, done as a promotion for Ford. I was producing the shows through Gilbert Marketing for Ford so Ford could get on the campuses and establish a presence with young people. The Mustang was a young person’s car.

At Gilbert I met Ron Delsener and we started the Central Park Music Festival, Kristal-Delsener Productions, which became the Rheingold, then Schaeffer, then Dr. Pepper, then whatever it is now. And the same year, 1966, I started a nightclub on 9th Street called ‘Hilly’s’ and we did improvisational theater and showcases. Bette Midler was in Fiddler at the time and performed in the club 70 or 80 times. I thought the club would be nice to do and would give me a certain foundation, where I would have my own place.

It sounds like you became involved with the club scene without it really being something you set out to do.

I wound up there because, as a singer, I had an agent on the West Coast and at one point we thought we would have a club together here. We had a location picked out and I was going to front it and sing folk music and whatever. But that fell through so when I heard about the job managing The Vanguard I took it and became involved with club management.

That was 1959, and the first group there was Miles Davis, second was Cannonball Adderly. Then Carmen McRae, The Modern Jazz Quartet, Oscar Petersen, Monk, Cortland, Lenny Bruce, Roland Kirk.

What an experience. Nice job. How did you wind up at CBGB?

Well, when I was finally over the hump and making a living I saw that on the Bowery, there was a whole art colony here. I mean there wasn’t any Soho then. There were about four or five galleries and a lot of artists living here. I happened to see it when I went to get some pots and pans.

So I decided it would be a great location to get two or three bars, artist and actor bars. I ended up getting one. This one, in December ’69. It was owned by an ex-prize fighter. But I didn’t started it as CBGB. I started it as ‘Hilly’s on the Bowery.’

Had the other Hilly’s closed?

No, I ran both at the same time.

Then they were contemporaries of the Fillmore East?

Yes. And the Electric Circus around the corner on 9th street. My club, though, was on West 9th Street. But I closed Hilly’s on 9th Street after a skiing accident because  I couldn’t handle both. Then I started another Hilly’s on 13th Street doing country music which I thought would be the next thing. Then finally, I couldn’t do both so I closed this place for a year. But I kept the lease. I re-opened in December ’73 and closed up 13th Street. Drove a cab in between

I couldn’t handle both. Then I started another Hilly’s on 13th Street doing country music which I thought would be the next thing. Then finally, I couldn’t do both so I closed this place for a year. But I kept the lease. I re-opened in December ’73 and closed up 13th Street. Drove a cab in between

The people on 13th Street gave us a lot of problems. It was a whole harassment thing and so I couldn’t have music. I was the first one that had to stop music. Then Reno Sweeney. Then Bells of Hell.

Was your interest in different kinds of music, whether it was country at one time, or jazz at another, or rock, based on your personal taste or your sense of the marketplace?

I love all kinds of music. I got into jazz and The Vanguard and liked jazz people and so when I opened 9th Street I was familiar with jazz, with show things, with everything. So it was an accumulation of all my experiences in music. Then if you see something happening in country music, and talent there, I think it’s kind of nice to try and make it happen. That’s what I like to do is try to make things happen. That’s what’s enjoyable in all this.

When we talk about a “scene” and you talk about Max’s and you and Reno Sweeney it sounds as if there was a sense of community back then. Was that the case?

Well I think that Max’s and I competed but we were friendly and communicated and respected each other and the fact that there were two of us benefited both of us. It’s like the three networks make it good for each other. Reno Sweeney’s, for a small cabaret, did a marvelous job.

Is there any sense of community present today?

Well there are a lot of things missing now. No matter what empathy I may have I’m not able to make things happen that I feel should happen.

But it sounds like in the ’70s there were other people like you helping to create the scene.

But there’s no focus now. There’s no scene. I’m busier now than before but that’s because there’s no other place that has good sound and where young people can come.

But the press certainly doesn’t come here. The Voice, and you can quote me, comes down very rarely. They don’t consider anything really happening. The Times? They write about it, they never come down. They write that something’s gonna be here, and they talk about how good it is. They never come down. They highlight jazz and they write about it and there are lots of jazz clubs, but they never talk about new talent.

I feel that they should do more than they do, but there’s another problem. Maybe it’s the fault of he press, the fault of the clubowner, the fault of the entrepreneur. But it’s more the fault of radio than almost anything else. Because across the board, all over the country, radio caters to Top 40 or Top 20 music.

But hasn’t that always been the case?

No. It wasn’t the case when I started. There were 60 or 70 stations that played new music.

Are you talking about a local or national phenomenon?

I’m talking about stations in Chicago and, for example, WBRU in Providence plays Top 40 music. They’re a college station, Brown University. Even college radio plays Top 40 music. So there’s a problem there. There’s a problem that’s been growing and growing.

But there’s another problem, and that’s with the artists. I think artists are now copying each other and they really don’t have enough to say and they’re not persevering in what they’re trying to say. They’re trying to be popular. They’re trying to be middle-of-the-road. I don’t think there are that many wonderful bands. There are a lot of very good bands that play music very well.

Are you saying the conviction isn’t there?

Conviction and something to say and conviction in what they have to say. There are a lot of very good bands but who wants to hear another good band?

That’s it. That’s right on e money. But it seems to me that when you have a situation where many clubowners, whether due to high rents or whatever, are basically not paying attention to the music, I mean I’ve actually had a clubowner say to me ‘I don’t care if you come in and throw up on the piano as long as you get a lot of people in here and they buy drinks.’ When you have that attitude in the marketplace how can the kind of artist you’re describing play enough to become financially worthwhile to the clubowner? You seem to be, although mindful of the bottom line, also interested in checking out the reality of what’s happening.

Yeah, but what chance do I really give to anybody? Here I finally give somebody, ‘Floor Kiss,’ the opportunity to play three weeks in a row. I don’t know what good it will do. So, big deal. They’re doing three sets in three weeks. Is that going to help? I don’t know. I can’t afford to do more. Why do you think people come down? Do you think they come down only because it’s CBGB? They come down because I book 30 bands a week and each has a small following. Pretty pathetic, huh?

Then do the economies of the marketplace, the high rents, ultimately destroy the club scene? Does this mean that New York City now ceases to be an influential musical community because of the Catch-22 economics where worthwhile artists cannot be given the opportunity to play with sufficient regularity to get the exposure to make them valuable to the club owner?

But I do give them exposure. I do because I’m able to manipulate in such a way, and because it is CBGB I can do a little bit more. But I can’t do enough.

Look, the Talking Heads may be the most important band that came, not only out of here, but that came out of that era. Maybe they’re responsible for all the people that got into music with a different kind of dance feel. But when they started here they had it all together in that they knew in their heads what they wanted. They had a lot of discipline. A lot of self-discipline. They practiced and they did what they wanted to do. And luckily they had a lot of friends from the Rhode Island School of Design. The Shirts also auditioned and had a following from Brooklyn.

When The Talking Heads auditioned the first time they had 30-40 people come. They called the press and they started to get press down and within a couple of times they planed, Rockwell fell in love with them and wrote a big article. Woolcott from The Voice, and everybody started writing about them.

In those days I only booked six bands a week. Two bands shared Sunday and Monday. Two shared Tuesday and Wednesday. And two bands played two sets a night, Thursday, Friday and Saturday. With six sets in three days they had a chance to grow. Then they’d come back in six, seven, eight weeks. So they were able to do six shows in three days. Isn’t that valuable exposure?

You’re saying you can’t do that anymore?

Can’t do that anymore. Also rents were cheaper. We only had a little money coming in but you could keep it going. And I supported what was happening. But now my rent is four times what it was then. And, as I said before, the scene became diffused. But now my rent is four times what it was then. And, as I said before, the scene became diffused. And I’ll tell you what else ÷ now bands don’t want to play more than one set a night. It’s too much for them.

Oh, come on.

Oh, come on. I’m telling you.

There’s another thing happening. There’s a bar band scene in New York City, where musicians play in several bands interchangeably and they’re not that rehearsed. They play three to four sets a night and they’re good. And it’s happening in small, neighborhood bars.

But that’s like a friendly scene and people go there and drink and throw the bands some money and bands play their own material and cover material, and they mix it up. That’s what was happening in London when this started happening here. It’s good but does it lead anywhere? But if someone has a chance to develop it’s good.

CBGB still has a kind of scene happening because it had only one thing going on. Here bands are basically showcasing for friends or record people but, unlike the bar band setting, bands can’t grow here anymore.

But again let me go back and put it in the hands of the artist. Look, I started as a concert violinist. How many classical people, when they’re at that point, have places to play? Why can’t a band spend a lot of time practicing and have that as their growth period, and so when they get to the point where they’re playing in public they should be very, very good.

Look, if the band is good I’d give them a chance again even if they don’t draw well. I put bands that don’t have a following in with bands that do all the time. But now it’s so cluttered. I mean there’s literally over 30 bands a week coming in here. And if I have only 10 bands what’s going to happen to the other 20? And then young kids can’t come in. I really feel people shouldn’t drink when they’re young. I don’t really feel that happy that I have to have a place that has alcohol for people to come and hear good music.

It’s fun to drink, but I wish I could have a place like the coffeehouses of years ago, where you could make a living. In fact, I have an idea. If you know somebody with a lot of money, I have an idea how they can make more money. But if I have a good idea I won’t put it on tape.

C’mon.

It’s a good idea but it needs some backing. But it’s a way for people to make a lot of money. I mean maybe do as much as some of these hamburger things.

That’s a pretty outrageous statement.

Well, I’ve thought about it a lot and in fact I have a location where I could try it out as a prototype.

Anyway, assume a band can play every six or seven weeks and maybe play two or three other places. They can play in this area three or four times a month. Or if four or five people save up and get themselves a little wagon and play in Jersey, in Trenton or upstate. Costs money.

When I was a singer I couldn’t play every place. You had to have a following. When I sang at Radio City I was a good singer. Everybody was going to make a star out of me. I didn’t tell you about that. Movies and everything. Yes. But most places, they wanted you to have a following. I had a few friends who would come but you couldn’t play and ask for money.

But in the days that we’re talking about didn’t people come to a club assuming the music would be good regardless of who was playing? Didn’t the clubs themselves have followings?

Yes, that’s true. But I tell people look, you owe it to me, to you. Don’t spend $100 on an ad in the paper. Just tell your friends to tell their friends to tell their friends to come. That’s what it’s always been about.

Look, if you are an exceptional artist, I mean out of the thousands of thousands maybe one-tenth of one percent. Patti was an exceptional artist. You know who  was an exceptional artist right off? Steve Forbert. I don’t know why he didn’t make it all the way. But he was exceptional. There are certain people that have a magnetism that draws people. I’ll tell you somebody exceptional in his charisma is Jimmy Gestapo of Murphy’s Law. He’s very charismatic. The band is okay but he has a certain thing that holds people in. It doesn’t mean they’re great musicians or that they have anything more brilliant to say. But they say it in a way that people want to hear it.

was an exceptional artist right off? Steve Forbert. I don’t know why he didn’t make it all the way. But he was exceptional. There are certain people that have a magnetism that draws people. I’ll tell you somebody exceptional in his charisma is Jimmy Gestapo of Murphy’s Law. He’s very charismatic. The band is okay but he has a certain thing that holds people in. It doesn’t mean they’re great musicians or that they have anything more brilliant to say. But they say it in a way that people want to hear it.

It’s that way in the theater. It’s that way in the movies or writers. They may not write with such depth but they have some magnetism in their writing. It’s that way in television. But that isn’t what we’re all about. That’s very special. But there’s something that’s just as important. That’s what gets people to come down in droves, but forget that. That’s not the most important thing.

The Talking Heads were not that way at first. They never were, really. But they had something that was creative and interesting that enough people were drawn into what they had to say and the way they said it. And this is really the essence of what I would like to do, whether in rock or anything.

So here are all the acts that come in and record companies come down and hear them and some almost get signed. And there are many reasons why they don’t. And probably a lot of the time it has nothing to do with them. It has to do with the A&R people. They’re not doing the most popular thing ever. ‘Cause right now you’ve got to be very, very pop.

But that’s nothing new.

That’s more true now than it ever was. Less people are getting signed because they have to get it on radio. And they can’t get it on radio unless they pay a fortune of money. There are not enough things being played on the radio. Radio is the real handicap. So after you’ve played here where are you going to go? So, maybe independent record companies. Maybe this is the future. I think if I have anything to say here it’s that people reading this should be very supportive of independent record companies. And supportive of radio that plays independent. Because major companies are not signing new bands.

They’re signing maybe one-tenth of what they were years ago. So this is the only way for creative things to happen. And, hopefully, the independents will sell some records and the majors will start to look at this and radio will say ‘well people are buying these records.’ I don’t know, there’s got to be some way to get people to hear the music that comes out of all these bands.

I’d say in any week there are four or five bands, maybe more, that are as good, and, to the average person who buys records, sound absolutely as good as any of the artists out there making records. Not all of them are unique now.

A lot of that has to do with marketing. Ten to 15 years ago you came out with a single and it was a hit and you could die on the next single and never be heard from again. Right now, if you sell a million records, unless you’re absolutely crazy or there’s something really wrong with you, there’s no way you’re not going to go on for two or three years if you never do anything much more than be very good.

A million is a lot of records.

But look at all the people who sell a million records or albums. Two or three hundred. And some sell two or three millions, five, six million. They never did this before. And I’m talking just in this country.

But as far as signing new artists.

They can’t sign new artists.

It sounds like you’re saying the frustration level is at an all-time high.

All-time.

And radio is primarily responsible as far as you’re concerned?

Obviously the record companies can’t buck radio. I mean they can’t make them play it. A record label would love to sign a new band because they don’t have to give them so much. But the cost is not in the production so much as in the promotion. In making the radio stations play it. If The Stones come out with a record every radio station is gonna play it. They don’t have to play anybody. Nobody has to make anybody play the Stones records or The Cars records or Tina Turner’s records, do they? Everybody wants to be the first to play it. Because they feel everybody in their 20s and 30s is gonna listen.

For the first time ever the media that enables you to hear music that is geared to older people. Because the Arbitrons are based on listenership of people who are older. Older people listen to radio. Why do they want older people? Because the only way radio can survive is get X dollars per minute for toothpaste. They don’t care about 12-15 year olds. They’re not consumers.

Why are they aiming at the older market now?

When FM radio started in the early ’60s what did they have to play except for new rock music? This is where this whole music, AOR, Album Oriented Rock, came from. And it was played all over. And bands made it just by being able to be heard on all these AOR radio stations. And that’s what all these stations needed to survive. It cost them nothing. They had one person disc-jockeying for six hours and a lot of records they got for nothing. But then they began to tighten up. And then more and more.

Why?

I don’t know. Because things went up. Prices went up. Or, maybe they found ways to make more money.

That’s probably it. When something’s really creative and exciting and it’s not that enormous a kind of thing and then it demonstrates the ability to generate lots of money, it attracts the accountants and lawyers and then the creative people disappear.

Well, look, cost of living was way down. And artists were suddenly selling a million albums. They never sold a million albums before. And then in the early ’70s, things started going triple platinum. And then 1978 was the biggest year that record companies ever had. They made more money than any other form of entertainment. More money than movies. More than television made.

Now go get a Billboard and see how many records are platinum, double platinum, triple platinum. How many are selling six million, ten million. Things are going even further. And that, again, is only in this country. What did Springsteen do, 10, 11 million? But Madonna did five million. Cyndi did six million.

Why did the numbers get so much bigger?

Because they’re better at marketing. And there are fewer artists and they can push them harder. And they’re getting more airplay for less records. But the record companies are not that happy with it.

You’ve used The Talking Heads as an example. But The Talking Heads really didn’t get much airplay until recently.

Yes, but a lot of people wrote about them right off. How many bands is The N.Y. Timesgoing to write about? They write about Sonic Youth which is much less melodious but they write about them. It’s taken a few years for them but they actually make a fair living doing their own music.

Tell me about your record label.

I started this because the only way a band can get out and be heard is for me to extend CBGB further. And the way to do that is to do the music here and record it and get it out.

Are these “Off The Board” tapes recordings of live performances?

Sometimes they’re live. I like the live feel. I like it to have energy. I don’t want it to sound dead. Sometimes they can do it live during the afternoon and we can do overdubs. So we try to get it as good as possible and have alive, fresh energetic feel.

I started doing the tape and album compilations so it could be played on college radio stations and I’ve had a lot of good response. Hundreds of letters from college radio stations all over the country they’re playing this band and that band. And when somebody writes about it from someplace else, other stations play them and other people are hearing them. So, I’m accomplishing, in a rudimentary way, what I intended to do which is getting these bands out where more people can hear them.

The next step is with Jean Karakos at Celluloid who has made me an offer to circulate CBGB; because he can do much better marketing and promotion than I could ever begin to do. He’s geared to do it. He likes the different product that comes out of there and he would do it in vinyl and cassette. And we can further a lot of bands. We can do between 30 and 40 new bands a year. Isn’t that nice? And that’s another step for a band to grow and give them incentive.

Do you have a staff doing the PR for you?

Well, I push the band to do it for themselves. I say, ‘You have to do it for yourselves.’ And I do it for them. I put ads in publications all over the country and it’s costly. Because when you put ads in Boston Rocker and Option and this one and that one, it costs money. And you don’t sell thousands and thousands of tapes. And you end up having to give groups a little here and few there, to give to their friends. You know so · (laugh).

It’s working and it gives the bands a chance for growth. That’s the other thing. Until they record, and record it well, and get it out there they don’t go on and write more new stuff. If you have good material and your friends like it and you play the same thing over and over for one year, two years, you may write new things.

But the most important thing is growth; is for bands to write 30 or 40 songs a year  and maybe 10 or 12 are really good. And every year they keep writing and coming up with new things and getting better. And by getting their product out they go on to write new things.

and maybe 10 or 12 are really good. And every year they keep writing and coming up with new things and getting better. And by getting their product out they go on to write new things.

So I’m trying to figure out how to do this and make a living doing it. And if things work out with Celluloid, and I think they will, it can all go even further out and be more saleable. And if I can stimulate things with what I’m doing then maybe other people will do more.

And maybe ultimately you can have an effect on radio?

Yes. I think it has to have an effect on radio.

What kind of music are you looking for on your label? Is there an identifiable style?

I would personally like it to be more creative and less formula, less pop. I would like to see a situation like in U.K. All kinds of records sell there.

Are there any new trends in music that you can see? Some places where it’s going to be in two years?

New things? All the A&R people wanted it to come back to this country and were looking for guitar bands. But I still think it’s a mix of guitar and synthesizer. I think the trash bands, hardcore and metal have made things interesting. I think some of the noise bands like Sonic Youth and Ritual Tension are quite interesting.

But I don’t know. I don’t see any trends. There’s no motivating forces. I don’t see any means of promotion. I think trends will develop, maybe, out of leaders that are similar.

For instance, you have a lot of this kind of country music transcending into some of the more minimal music. Well, if one of them was exceptionally charismatic and talented, then you’d start a trend because there’s quite a few bands doing that kind of thing. But it’s staying with the independents and not becoming a national trend.

Do you see any one band that can generate that thing in that style?

No. I see some bands that seem as if they might but they haven’t really gotten it together enough. I haven’t heard any that have it all the way.

It’s difficult for trends to develop or a scene to develop because things are so different now. There’s a different importance now. People have learned how to make a lot of money doing things that are strictly commercial, that are strictly good in a business sense. Clubs know how to make money by starting, doing it disco, and spending a lot of money, and it doesn’t relate to music. It relates to people coming and having a good time. And if there’s music there it’s not the basis and nobody knows who’s playing or what’s playing and it really isn’t even important. It’s just important that there is sound, that the rhythm is great and all that and that’s wonderful. Those are happening things but it really doesn’t relate to new trends or the development of music. And I don’t think writers are that impressed with the things happening in rock.

Are they justified?

Well, yes. But yet when I think of how many things I have to listen to, I mean are they gonna have to wade through thousands of tapes or hear all these bands? It’s too much to hear. Where are they gonna hear them all? I mean there’s too much to hear.

Are there other cities that have a music scene happening?

Sure. Austin, Texas a little bit. The N. Carolina thing. Basically because of producers around there. Atlanta has some stuff. Boston has always been a big city. Always been supportive . See Yew York is not supportive of the talent around here. Boston is.

But isn’t that because so many people who want to get heard come to New York and it’s just too cluttered?

I think there’s too much happening in New York. Too much that’s very good. I mean if you’re in Madison, Wisconsin you’ve got a big school and some local clubs and a chance to develop. And also, the tendency is not to copy what is happening in the same way others will. Somehow you’re living in a dorm or at home or things are cheaper and you conform less to what’s happening so maybe you’re a little bit more original. Maybe you can see the earth and the water and the sky a little bit more. Maybe that can contribute a little. I don’t know. I think living in New York can have its handicaps.

Then again there’s the problem that people just don’t work hard enough at what they’re doing. I know more musicians that really don’t work hard enough. There’s a lot of talent I know of that could make it. I’ve worked with a few people that I know if they really worked like anybody should if they were really an artist or musician, they could have made it. They don’t know it but they’re dilettantes. They don’t know what work is. And that’s the problem with most of the groups.

You sound like my parents.

Well, I keep coming back to Talking Heads, David, Tina, Chris, Jerry. They worked hard. I’ll tell you another group, Blondie. They were discovered and they became very tight musically. They worked very hard and so I think they deserved their success. There were others with the same opportunity who didn’t do the work. The Police, another band that worked hard, rehearsed, worked, wrote. They were together. They toured all over the country in a van. They worked hard.

You have to keep working at what you’re doing and believe in it. It didn’t happen easily for these bands. I know more groups that probably should have happened but they didn’t work at it. They just wanted the outward manifestations of what it means to be a celebrity or a minor star.

Most people would say you need a craving for celebrity and for audience approval?

I don’t know. I just don’t know if Debbie Harry ever had that craving. The Ramones enjoyed doing what they were doing. David Byrne didn’t seem to have that kind of personality. The Police were enjoying themselves and worked hard. I don’t think a lot of groups have that craving so much as they enjoy making music together. Of course it is enjoyable to have people applaud you. But most people in rock are not entertainers.

Look, today the music business is the record business. And if people really want to make it they have to work and play hard for themselves. And they have to do it by being introspective. And they have to realize that if they have something to say they have to figure out how to say it so they can move people in some way, to excite people.

What’s OMFUG?

Other Music For Uplifting Gourmandizers.

Come again?