Music Distribution

We are currently experiencing some short-term hiccups with our physical CD distribution: in the meantime please click on the album links on our Albums page and hit the Amazon buying links to check if your title is available .

Download sales continue to be available via the usual services and you can also still stream our music as usual.

Music Distribution

We are currently experiencing some short-term hiccups with our physical CD distribution: in the meantime please click on the album links on our Albums page and hit the Amazon buying links to check if your title is available .

Download sales continue to be available via the usual services and you can also still stream our music as usual.

Marc Almond: Fantastic Star

Recorded by Mike Thorne at the Stereo Society, New York, and Harvey Goldberg at Skyline Studios, New York

Mixed by Harvey Goldberg and Mike Thorne at the Stereo Society

Assistant engineers: Valerie Ghent, Laura Janisse, Miguel Lopez, Jason Tal

Recorded by Mike Thorne at the Stereo Society, New York, and Harvey Goldberg at Skyline Studios, New York

Mixed by Harvey Goldberg and Mike Thorne at the Stereo Society

Assistant engineers: Valerie Ghent, Laura Janisse, Miguel Lopez, Jason Tal

Marc Almond: vocals, percussion

BETTY (Alyson Palmer, Amy Ziff, Elizabeth Ziff): backing vocals

John Cale: piano

John Coxon: keyboards

Larry Etkin: trumpet

David Johansen: harmonica

Ross Konikoff: trumpet

Morton Street Local 10014 (Daisun Cohn-Williams, Adam Honig, Dylan Kenney, Nina Svatovic): backing vocals

BJ Nelson: backing vocals

Rick Shaffer: guitar

Chris Spedding: guitar

Mike Thorne: keyboards, rhythm

Neal Whitmore: guitar

For permissions reasons we are unable to offer streaming audio of the New York session mixes

article by Mike Thorne

click on section name to skip down

1 Why Tell The Story?

We all need regular reality checks, like yearly visits to the dentist. When you’re flying, you have to remember where down is. In that spirit, as part of a book to be called Music In The Machine, I sketched a long chapter to be called Losing It or Failure. Instead of the glorious, accoladed and embellished successes that are the usual feel-good showbiz stories, I would write of personal experience of failure and, most helpfully, indicate the reasons why things went wrong.

Things go wrong, shit happens. Even though we all prefer success at all times, there was a story to tell through two particular projects. My gory examples, each having very different reasons for collapse, would be Marc Almond’s Fantastic Star, which shone so brightly for a while, and Marianne Faithfull’s unfinished Sexual Terrorist. (To do justice, I would have to speak to the unsuccessful album protagonists. I knew Marianne wouldn’t hesitate to talk, but I expected that Marc would prefer not to.)

These had been two potentially world-beating projects. I still feel the New York version of Fantastic Star is one of the best career efforts from Marc or me, individually or together, and regret the waste of good music and exciting, creative time. Terrorist was temporarily abandoned in 1985 when Marianne hit bottom suicidally and had to go into instant rehab. After a promising but tired restart, it was finally canned by Island Records’ boss Chris Blackwell. (By way of atonement, I covered Marianne’s previously unreleased songs Self-Imposed Exile and Sexual Terrorist in 1998 on my own Sprawl, with vocals handled by Sarah Jane Morris.)

What was to become Marc Almond’s Fantastic Star CD was one of the most disappointing results of my whole commercial record production career, which it concluded. Its particular evolution seems one of the worst examples of the contemporary self-destructive malaise of the non-creative side of the business and the disposability of music and musicians. As Marc and I worked on the music, weathering unexpected and debilitating interruptions and roadblocks from the record company and others, we usually both felt like two children playing in the sandpit. Our relationship during nine months of recording together was unusually constructive and creative, and we came to trust each others’ judgment and integrity in what seemed for a while to be a perfect collaboration.

At the beginning, I sensed the team might generate a classic record. I had already decided that this would be my last commercial, or hired-gun, record production, a quality-of-life decision and relished the possibility of kissing the profession goodbye with a big bang, with a distinctive, enduring piece of work.

At the beginning, I sensed the team might generate a classic record. I had already decided that this would be my last commercial, or hired-gun, record production, a quality-of-life decision and relished the possibility of kissing the profession goodbye with a big bang, with a distinctive, enduring piece of work.

My notes run from October 1993 to July the following year, when the project was shipped off to London. They would total 23,519 words, in abbreviated form, about 60 printed pages. Going back to them with the insight of retrospection, I can see why people are driven to keep daily journals, but I’m not about to start. You may put it down to laziness. But I did it this time, because I thought we were living and creating a good story. The result is a far longer production essay than others on this site, but I hope it will reveal more of the music-making process through its mass of supporting detail. It’s a day in the life of a record producer, lasting nine months. In the end, all would be cliché. The bang would become a whimper. This would be Marc Almond’s lost album.

My idea was to write the book of the album, even though for practical reasons it could not be published as quickly as the record. As the project progressed and sounded increasingly special to me, I thought that the CD would have a long, celebrated life and the book could be published while it was still current. The recording eventually smeared over two years (after the nine months with me), three different A&R men, two record companies, multiple producers and, consistently at least, one manager.

The practical minutiae of a big recording project are usually dull and seldom noted. So many people are dying for an invitation to a recording session, to sit at the back of the space-age control room and thrill at watching artists-at-work. Unfortunately, the spectator experience is rarely dynamic. You watch a half-dozen intense people too busy to chat with you talking in a language you don’t understand. They argue passionately about issues such as feel, tuning and rhythm whose variations you can’t hear. You can’t even begin to understand what the heated controversy might be all about. Even when outsiders are present, without deliberate exclusion, action remains esoteric. The slaves to the music might not have developed their patois to keep the plantation owner ignorant of their conversation, but the effect of the intense, detailed focus is similar. It’s a private world, and usually remains so.

However, this huge body of written record, much of it to do with arcane and exotic processes, seemed valuable to me, maybe even unique, when I returned to read it ten years later. I hope it’s accessible by you. You will feel the music production standards: alternate boredom/grind and exhilaration, the swift changes between frustration and triumph/satisfaction which are typical of commercial recording with all the forces bearing on it. You might well feel as if you are that confused visitor at the back of the control room. But at least you can share the switchback ride. It was bumpy for us all.

Marc Almond singing on the Skyline session, Friday April 8 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

Marc Almond singing on the Skyline session, Friday April 8 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

Before starting this article, March 13 2004, I have never listened to the final CD issue of Fantastic Star from beginning to end. I will do so after finishing, remembering Marc’s and my enormous delight and satisfaction at the conclusion of its New York phase. Memory should not be colored just yet.

By accident, I erased an ecstatic phone message from Marc some time on the last warm Saturday night in 1994 after we had finished and gone out to play (well into Sunday morning, both of us out on the town). It was a picture postcard from a wonderful place.

We had great reason to celebrate. I’m now at sea in mid-Atlantic between Tristan da Cunha and St Helena. Maybe the old Soft Cell would feel that this producer Napoleon is heading home (Boney was exiled to St Helena until his death). In a couple of days, we will see where the great monster went out with his whimper. And then return to New York to lay other ghosts to rest.

2 Beginning

The public at large, if it has any opinion on it, probably sees the English record business as some small scale version of the classic Hollywood Busby-Berkely movies: a glamorous, well-oiled, if rather fashionably cynical machine that is tirelessly assembling and marketing the next crowd-pleasing round of popular hits. Allied with a folksy element of ‘let’s do the show right here’, at which Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers were very good. Clearly, there must be an efficient way of finding talent and assembling supporting casts to make a great, innovative records that can appeal to a broad sector of the population. The record business doesn’t use it. Precedent is all. New, different music has to stake out its turf without any historical support, by definition. Survival of the fittest applies.

Tainted Love was the early eighties for many people, now a long time ago, and my working relationship with Soft Cell disintegrated in a mess 18 months or so later. Over a decade later, my reconnection with Marc Almond started with a relatively routine letter to Rob Dickens, then the boss of WEA Records in Great Britain. The music business functions almost exclusively and most smoothly through personal contacts, and they wither if left untended for too long. Back came a friendly fax saying, ‘stop by next time you’re in town, and by the way Steve Allen has joined the A+R Department here and has already proposed you for a project.’

More small world: Steve and I had known each other for many years, beginning with just after his post-art school stint singing in front of Deaf School and Original Mirrors. For a while he had even lived in my house in Camden with my ex-girlfriend Jo. One evening I had arrived off the day flight from New York (to work with Bronski Beat) and stumbled tired down the kitchen stairs to find Rob, Steve, Jo and a half-dozen others: a serious party in progress.

The showbiz meeting ground of the Hollywood pool party, moguls and mayhem, cocaine and cigars, bimbos and brandy, has different versions for different places and cultures. And different levels of crassness, of course. They’re all geographically distinct, even in a global entertainment world. But all of music business depends on a that, sometimes uneasy mix of social networking, different in different places. It’s often cynical but can, truthfully, be pleasantly and genuinely social.

The smaller the place, the closer-knit the circle. And a Camden kitchen is more comfortable than the pool in an English February in a rattling house at the top of the hill. In New York, people go out more and the scene tends to be more public. In Los Angeles, ya gotta have a pool. Nine years later, in 1993 in my Notting Hill kitchen, it turned out that Marc Almond had an album to make. Change was in the air for both of us. We would be told that we had to/could do something different, we had to find ‘the new Marc Almond sound’. This sounded very promising.

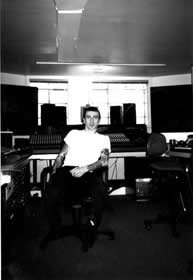

Neal Whitmore relaxing with the session mascot, cardboard Elvis, late 1993, photo: Jo Dawkins

Neal Whitmore relaxing with the session mascot, cardboard Elvis, late 1993, photo: Jo Dawkins

I initially met with Marc in the second week of August 1993. The artistic fit was instant and close. We had missed each other, had experienced separately (and differently) the burden of the massive hit that Tainted Lovebecame, and it was immediately obvious that we could do good things together. Any conversational lead by either of us seemed to find perfect resonance and pickup with the other. I remembered why those antique Soft Cell records continued to sound so good and why they had been so satisfying and stimulating to make.

Again, the small world comes around again. I call a few friends in London, having finally emerged from the monastery of the previous week’s recording sessions with the new incarnation of Bronski Beat, and recovered from the tiredness which comes from landing 3000 miles away after no weekend then going straight to work the following day.

One social call is to Sarah Jane Morris, formerly of the Communards who, among her typical plethora of wildly varied potential projects, is short-listed for a major supporting role in Les Misérables. More small world connections and coincidences follow. Since working with Frances Ruffelle on a single for Children Of Eden, we have become very friendly. Her former husband John Caird was co-director of Les Misérables, and she herself won an Emmy for playing Eponine. Two calls later is to Frances’ answering machine, and she returns the call within 15 minutes. Dinner follows 45 minutes later. Frances is close to a deal with Warner Brothers Records, with Rob Dickens as the boss of the major interested party. Round and round we go. And that was just keeping my head down with real friends. This London-small-town syndrome is so comfortable and supportive. The downside, as we’ll see, is that small-time thinking can occur.

Eventually, after what seems an eternity of chin-stroking and profound consideration by the powers-that-be, Marc and I were given the go-ahead, but told to record just four songs and mix only two. Not exactly artistic license, let alone room to grow. Such was the shell-shocked and gun-shy caution of the English record business that they couldn’t even frame the project in the larger structure of a staged and timed album delivery (and such caution would become far more constricting later).

Instead of planning the album production in stages, as in the good old days, cautious business and ‘marketing’ now decreed that the creative team should make a few sweet offerings, wait for thumbs up from on high, then judder back into action and line up for the next step. Real people don’t resonate with such rhythms, and I would argue fruitlessly that this was a draining and financially wasteful process. I could have steered through a great album for $100,000 of total production costs, including Marc’s travel and lodging, on a schedule which would have permitted evolution of the desired new sound (of which more later), with a chance to breathe and develop organically. For a dithering and potentially compromised first four tracks, we were looking at spending at over a third of this amount.

Rick Shaffer and Neal Whitmore recording guitars on Out There, February 1994, photo: Molesworth

Rick Shaffer and Neal Whitmore recording guitars on Out There, February 1994, photo: Molesworth

Britain used to be a net exporter of music, often overwhelmingly so. The US still refers with respect to the ‘English Invasion’ of the sixties. It was generally true that the industry could not survive, given its relatively small local market and the increasing costs of launching a mass-market CD, without bounty from abroad. But UK executives would typically just release locally and build out from there. Executive careers are not made quickly on long-term international success, but rather through more visible local success. Crippling introspective complacency often results. The process is nothing new, and I had first grumbled about it on arriving at EMI Records in 1976, shortly before the Sex Pistols.

3 Gearing Up

In large-scale deliberations by industrial management, great importance is put on workers’ ‘morale’. Could that mean a cricket team on Sundays, or not having to punch the clock? These are side issues. Separating the fulfillment of a task from a person’s own sense of personality and worth is ever more prevalent and poisonous, whether the worker is sweeping the streets or posing as President of the United States. The separation of the substance ‘work’ from the ‘worker’, supports the pretense that work can be an abstract, measurable commodity, is central to Karl Marx’s comments on the alienation of labor. We don’t function that way, in my experience at least.

The wrenching separation of peoples’ identities from their work, which was an eventual consequence of the industrial revolution and some applied science (such as time and motion studies initiated at Bethlehem Steel in the US), happens to crazy musicians just as much as steelworkers. Now, it may even be that large industrial companies are more sensitive to their human resources departments’ concerns than are record companies (such as they remain) whose very resource is always ephemerally human.

Seen from the outside, the apparent whims of artists are often hard to understand, or sympathize with. (The tabloid press loves indulgent collisions.) So are holding on to your childhood teddy bear, raising a laugh with a catch phrase, or any one of those gestures which let you belong. These little things give us comfort and continuity, and you carry them with you. I forget which major person commented: ‘Carry my culture with me.’ You do. You carry your personal cultural center.

In the real outside world, we dare speak of context, we grapple with how things exist in the environment that surrounds them. If you’re a singer, whose mental processes are exposed to the world at large, you need to feel very comfortable with yourself to deliver the perfect lead vocal. You need your own solid internal context. And you need to be in the right mood. You will need a few personal rituals. It’s a license for indulgence and one that has been granted too many times, but a successful, communicative artistic end result can almost justify the means.

Imagine: you’re your own fragile, physical instrument (given). Right now you don’t feel a reflection of the sentiment of the song which you yourself have written, it’s 3am, and the record company says it needs the record the day after tomorrow. Further, the studio you are recording in costs $2000 per day, and you’ve run out of credit, as your manager pointed out this morning when he woke you up 16 hours ago before you were ready for consciousness. That is fragile. Anyone could use a familiar reference point in such a skewed landscape. For a singer, that generally means ensuring that you have a consistent support system.

Marc’s manager was Stevo, who had used idiosyncratic whimsy to disarm and even charm the opposition in the typically adversarial relationship with the record company. After the collapse in the same week of creative relationships with The The and Soft Cell, which I attributed at the time to Stevo’s inappropriate management machinations, I had resolved to have nothing to do with any of his acts no matter the quality of artist or music. But that had been eleven years before, and I thought that people could learn, and should be given the benefit of the doubt. Stevo came over to my London apartment. We talked pleasantly, if slightly guardedly. I decided to let bygones stay so. Let’s go and do good things.

4 Setting Up

The business imperative in effect at the start of any recording is obvious and routine. We now needed to set Marc in an environment most helpful to making a record and delivering the best vocal performance, to create something original and fresh without compromising ‘the integrity of the artist’. The financial precondition is that it must touch the hearts of millions of people with $15 rattling in their pockets. Here’s the next issue, even more basic than whether you are pandering to a commercial chimera or aiming for a personal ideal: you sang a song tonight which made the hairs on your forearm rise. How do you judge it? For the singer, there’s no avoiding being on the spot.

Can you do better tomorrow? Try again now? The producer, me, has run out of tracks. Do I erase the first take? Might that be the best, the freshest? Can we tell anything objective at all after slogging through all the musical development to get where we are? That’s more than 10 seconds of thought, the time it takes to rewind the tape for the next take (here, in 1993, we are now recording vocals directly to computer disk, and the rewind time is close to zero). But Marc and I are to be given a very short, sharp set of New York sessions. There will be little chance to enjoy retrospection and come around to a superior new concept or approach to a song. It will be a harassed 3am for both of us for most of the time.

Under such immediate pressure, where would you set the bar? Imagine the singer, physically alone in the studio or psychologically alone under the spotlight. We call a classic performance priceless. How much will we spend to get such a performance recorded? How many punters must buy it for the bottom line to be black? And who will use that fuzzily all-purpose word: ‘priceless’?

Under such immediate pressure, where would you set the bar? Imagine the singer, physically alone in the studio or psychologically alone under the spotlight. We call a classic performance priceless. How much will we spend to get such a performance recorded? How many punters must buy it for the bottom line to be black? And who will use that fuzzily all-purpose word: ‘priceless’?

And then, who is the judge of that performance? Is it the punter, with $15 or more in pocket, six months in the future? Is it the record company, just one week later, who hear something in rough, frozen form that they love/hate and so commit/withhold marketing and promotion dollars? Is it the artist who returns exhausted to the control room to listen to a few tentatively preserved takes? Is it the producer who can, for energy economy reasons, decide to stop the whole vocal take after ten seconds if it seems not to be going anywhere (and thus maybe ruin what in the singer’s ears would have been the ONE)?

At what point may we find a measure, a reference, any sort of reliable guide? It’s not an easily quantifiable business, admittedly a big part of the attraction. Even after years of experience, for all of us the whole operation progresses by the seat of the pants, not through regressive marketing extrapolations with their boy-band termini whose justifications sound so good in high-level meetings. When you’re doing it, you often need a little time and distance to judge how good or bad is your work. And then what to do, if needs be. New stuff doesn’t come in an easy container.

5 Getting To The Music, At Last

At first, everything had seemed set for us to plan an album whose shape would unfold over three careful months in New York. Inconveniently, Marc felt written out when the initial songs on the table were declared not yet to the record company’s satisfaction. His creative muse, let alone his sanity, wasn’t helped by living in the middle of remodeling his new place in Fulham (it was routine to be on the phone with him from New York and hear him pleading for, ‘please, just five minutes’ peace and quiet, please, please.’). Meanwhile I started assembling the downtown recording team. We had been told to find a new sound, to get away from Marc’s over-used cabaret and synthi-pop sonic backdrops. This sounded very promising, adventurous and exciting to both of us, a genuine license. We had license.

The new rhythm style was to be strong, simple guitars over a power-techno rhythm. There were already some suggestive demos to hand, developed with John Coxon, Steve Nieve (he of Ian Dury’s Blockheads and Carmel’s Bad Day sessions) and Neal Whitmore (previously of Zigue Zigue Sputnik, a punk/glam band that didn’t quite pull it off but created a few nicely inspired fun waves). Whatever the horror of Marc’s domestic mayhem, his writing flourished, and he shortly delivered his breakthrough in demos of Jealousy and Addiction. These immediately qualified for the top ten, in our minds at least.

For some weeks, I had been in New York laboring away on other projects as negotiations between Marc’s and my managers and the record company proceeded in tranquilized slow motion. With embarrassing timidity, the record company now insisted again that we record just four tracks as a pilot then pause for appraisal. This might seem efficient on corporate paper in the bean counters’ offices, but in the studio at the bottom of the food chain it can be next to impossible to get any momentum going unless you set up a strong developmental sequence of music-making. Moral: to make an innovative record requires boldness, and not just from the artist. And you need a run at it.

We face the reality of this grinding pop music business. I hate the formal idea, but have no choice since I would like to work with Marc and his music. My management insist that two tracks will mixed, since none of us even dreams that the record company executives have the ability to hear through an unfinished recording and imagine a completed, mixed record. Over my nearly 25 years making music recordings I had seen record companies become steadily more ignorant of the methods of production, even down to the A&R (Artists & Repertoire) departments who in earlier years would have even have been physically making them. (As I complete this article, in 2005 there are even fewer musically literate A&R executives remaining.)

Whatever the inauspicious omens, a deal is cut and I resume assembling the New York repertory company, scheduling preproduction sessions with Marc in London. During this phase, we participants will work on the material away from the expensive recording studio environment, formulating anything from song keys and structures to rhythm patterns and instrumentation. I meet Neal Whitmore, linking again into the small London world since he is living with Katrina, a London Records A&R assistant I knew well during my sessions with Bronski Beat, Carmel and the Communards among others.

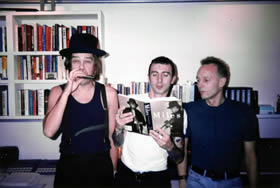

David Johansen, Marc and Mike Thorne, April 27 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

David Johansen, Marc and Mike Thorne, April 27 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

Saturday October 23 1993, I return to New York. Maybe it’s cosmic writing on the wall for the future of the project when I get a phone message from my studio landlady on the following Monday, the first recording day of the project. ‘It’s time you fixed the noise problem. Like by leaving.’ My studio assistants have been careless in the middle of the night. That wonderful guitar sound recorded for the Nitecaps, bouncing off the brick wall in our basement and up to their bedroom, had woken the couple on the third floor in the small hours of that Monday morning. They were tolerant neighbors, but that noise would have blown it for me too. Sometimes you just think that New York is stacked against you when you try to do anything. Comfortingly, perhaps survival of the fittest means that things come out tougher after overcoming a little extra resistance. I don’t take the long philosophical view, but just put out the local fires.

Neal has come over with Marc as his advance guard. As well as being the songwriting half of many of the songs, he provides Marc continuity, a reference point in his big change of musical environment. Such dislocation can easily shake the most experienced of people. Looking back over my notes, which I forced myself to make every night after the session even if eyes were red and barely half open, I’m impressed by the ground we covered in the first stage. Three coiled springs were released at last. On that very first Monday, the product of so much planning and scheming, I leave the studio at 1.30am, and adrenaline lets me sleep only four hours, finally denying me rest at 6.30am. We had started all four songs: The Idol, Rise, Addicted To You and Jealousy. Being the basic electronic rhythm department as well as the production glue, I’m working very hard.

The repertory company is falling into place neatly. Rick Shaffer, formerly of the Reds, who conveniently lives five blocks from the Stereo Society studio and is one of the best guitarists I have ever worked with, is around and keen. I cut a deal with Chris Spedding for him to come in from Los Angeles for a few days, thankfully (and providentially) at a lower rate than his manager would have insisted on in the eighties glory days when we had worked together on albums for Nina Hagen, Kit Hain and Roger Daltrey.

It’s good to have one of the most respected guitarists in the world on board, and Neal is really excited at the prospect of meeting him. I regret to disappoint John Carruthers, another fine expat Brit guitarist living in the West Village, since Marc observes that the guitar department is getting a bit out of control. He’s right. The section is now three top-rate exponents, whose styles complement each other nicely.

The real fun starts on Friday. It’s always something. Marc comes down with gastroenteritis. A major scheduled gig in Mexico City, to which he would have just hopped to and from, has been canceled. Neal and I go to his rented one-bedroom apartment on Christopher Street and find him propped up in bed surrounded by three raucous friends from London. Even though happy, he does look a little green. Neal has completed his remaining guitar parts, the only hard deadline of the day since the forecast is heavy rain and he’s keen to get home to the beautiful Katrina whatever the airlines’ vagaries. Marc has the Thursday mixes.

Marc: ‘If the record company doesn’t get this, I don’t know which way to turn.’

Neal: ‘The tracks keep all the good elements of the demo but take them further already.’

Mark (London friend): ‘Amazing to hear this at the end of only one week. Sounds as if you have been enjoying it in the studio.’

As we had, and it comes through loudly

We listen to the cassette of today’s efforts, and it sounds ghastly. The neighbor downstairs clearly agrees, having come up to complain about the noise. But we know we are on our way, and my hopeless, off-kilter mixes are simply a reflection of an obsessive guitar day after which, having lost perspective, we typically mix that focus instrument either too high or too low. Reality check is always helpful, though, and this one keeps us from getting too lazy and over-confident. I go out to dinner with Leila and we play them loudly on returning. They’re still awful. We get to bed at 12.45am and I sleep for twelve hours straight.

After a resonant New York meeting with Sandra Bernhard, the confrontational feminist comedienne/singer, I had been tentatively scheduled to travel to Los Angeles to meet her band. Fortunately, her schedule slips, so Marc and I can now take full advantage of the excitement and momentum. I get on the phone and lock in a few sessions and, although preferring always to avoid contaminating weekends with work, I go into studio on the Saturday. Turns out that communications haven’t ended with the business week.

The record company has drawn the check on the wrong account and their fax wants it stopped. The air conditioning installer turns up to pick up his promised payment with what seems like his entire extended family in tow, transforming the cool studio into instant madhouse. Marc and I are overwhelmed by all this financial shambles in just one day, another marvelous omen of our coming wealth and fame.

6 A Second Week

The second Monday of the project duly arrives: November 1st, a date that smells of impending winter and cold. Marc and I are moving slowly after our respective strenuous weekends, but we start looking for local female backing singers for Jealousy. I play him a tape of a recent effort with Genya Ravan, Don’t Let Me Down. He doesn’t like her big, belting style, since he is looking for an older, more reserved and troubled black sound. Fair enough. But I become slightly concerned, having reserved the three-woman group BETTY for a slot there. We’ll just have to see what falls into place.

Singing, and choice of vocal partners, have few rules except those of the leading artist’s intuition. It’s very personal, and you don’t argue. But I play Marc some BETTY recordings and he really likes them. They arrive in the afternoon and drop the first backing vocals of the album on Jealousy, a contribution which will survive all the way to the distant, mangled release CD. We try them on The Idol with less success. They’re not innocent enough, Marc thinks. Fair enough again.

Chris Spedding on the Skyline session, April 8 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

Chris Spedding on the Skyline session, April 8 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

We’re still keeping up the construction pressure. Rick Shaffer arrives for the evening session, and he and Marc hit it off immediately, trading shared musical passions and prejudices. Rick contributes carefully to Jealousy, notably a rockabilly lick which will survive to conclusion. Having delighted us with the music under the fingers, he then tells an extended anecdote about rockabilly band misbehavior on glue, cough syrup and booze, in utter contrast to the quiet, intensely sober focus in the control room.

All of us have relaxed and loosened up as the evening has worn on. Rick is let loose on a free, unplanned run at Rise. He hits the perfect chorus big crash chord and Marc and I both sit up very straight. 20 minutes of spontaneous high intensity gives the three of us a slew of new ideas.

By way of keeping me from my bed, I have to write an arrangement for four trumpets on this track (to be played by Larry Etkin from the Uptown Horns and associate Ross Konikoff at 2pm tomorrow). Once again, I’m flattened after such an energetic session and therefore put the scoring off until the following morning. Homework is hard work.

Another adrenaline-shortened night’s sleep helps get me to get going earlier than I would have liked on the Tuesday trumpet fanfare, but I’m not done until 2.15pm. This is before computer-assisted scoring, and writing for transposing instruments doesn’t help. (For historical reasons to do with the physical development of the instruments, when a trumpeter plays and reads a C, out comes a B flat. A written C can sound an E flat (alto saxophone), an F (French horn), a G (alto flute) an A (some clarinets).) The trumpeters play on one microphone, balancing themselves. Always nice to work with top-shelf professionals. For the remainder of the day, Rick contributes elegant guitars to Rise and Addicted.

We work through the week. On Friday I do four rough mixes of the story so far for despatch by courier to London so that the record company can inspect the damage. Jealousy is still a bit of a mess, so the rough takes 2 1/2 hours. Others are quicker, because the arrangements play themselves better. They’re ready half an hour before the courier collects, as always a deadline focusing the mind clearly, and especially with the weekend looming for us all. In my case there is studio with BETTY on Saturday and considerable homework to do on all Marc’s tracks.

Monday November 8th arrives with Marc and I slow and tired as usual. We’re both very irritated by the complete radio silence and lack of reaction from London (Marc in particular is mad that Stevo wasn’t banging on Warmers’ door at 10am), and my hothead inclination to send a caustic fax at the end of the day is sensibly cooled by my manager Mark Beaven. The same dead quiet prevails through Tuesday, and we’re both getting ticked off by the lack of consideration. We all have planning to do. Perhaps the distant controllers can get off their fat asses for 20 minutes to listen and decide. I propose taking a long weekend rather than fiddling about in a vacuum.

Neither of us wants to slow down, but the lack of any feedback puts us in an ungrounded position. I expect to go over the studio budget by just one day ($1000), in an industry where 50% would be fairly normal. The New York Warner office is also getting irritated because they need clearance on Marc’s apartment rent check (every little outgoing has to be sanctioned, since apparently they don’t even trust Marc with his launderette change). Can we have just a little shred of executive autonomy here, or will you please change my diapers now? New York also thinks the roughs are terrific.

7 The First Slip

Eventually, we discover that the fax from London had fallen off the machine tray, to languish for three days on the floor behind. Thanks for the encouraging and constructive call, pals. The words are unremittingly negative, devoid of any constructive suggestions for improvement. Steve Allen, the UK Warner Music A&R man, is clearly hiding behind this half-communication fax medium, and doesn’t care for the confrontation which would result from a telephone call. I show it to Marc, who remains unusually composed. He asks for paper ‘on which to write a fax’ and I leave him alone. He is very good with words.

As a more positive displacement activity, I remove to the control room and start polishing a few bits of musical brass. Marc reappears with a brutally ad hominem fax. (Out of consideration for Steve, we don’t post Marc’s minor masterpiece here.) Perfect theater is achieved by his proposal to send it repeatedly until the company’s paper is all out. The only constructive contribution of the Stereo Society institution is to type it to improve legibility. We all have a good belly laugh at this juvenile rock+roll brattiness (….how old are we?) and on calming down realize that Addicted sounds pretty much finished.

The heads-down-defensive fax still gave us some unwitting clues, and we proceed to fix The Idol in 30 minutes flat. I had got the bass line wrong. Done. The feel is back to the original demo, which was great and had proved elusive for a couple of weeks. The floodgates are opened for us, and all sorts of good things achieved. It would have been better had they been started earlier. Marc is on the phone for a long time with Stevo, who claims credit for some incredible political move, although this New York crew treats his claim with some skepticism.

How we wish there could be discussions with an intelligent record company presence, rather than this ponderous handing-down of stone tablets from the mountain. Maybe it reflects their technical insecurity and their apprehensive perceptions of Marc’s volatility (he is good with words……). It’s all too mysterious and distant, existential for some. We have a record to make. Or used to, at any rate.

Further studio improvements early Wednesday morning bequeath us cement chaos all through the studio and utility room. Another New York thing. I hear from manager Mark in Chicago, who had spoken to Steve Allen who ‘didn’t get the charge from the roughs that he had been hyped to expect.’ Did they expect a finished record? A charge from a demo? I should make demos for a living.

Recording the kids for The Idol, April 25 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

Recording the kids for The Idol, April 25 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

It’s the same old syndrome: the controllers want progress roughs but don’t know how to extrapolate and end up disappointed by the unfinished record. Marc’s fax has ‘gone down very badly’ in London, but he’s utterly unrepentant and I’m delighted. It’s just like the old, carefree, irresponsible days. How self-important can the music moguls be, anyway? How has the world grown to be so leaden? Can we take ourselves less seriously once in a while? Are we having fun yet?

Another head-below-the-parapet fax from Steve Allen complains about my showing Marc his fax to me. What did he expect? A phone call could have been unrepeatable confidences if requested. Is someone pulling his strings, or is this just social incompetence? I have learned from bitter experience that if the political signs don’t make sense, then there’s usually a hidden agenda. There must be several to create this big, confusing mess.

I speak with Harvey Goldberg, one of New York’s top recording engineers, with whom I have worked closely for many years. He offers to mix The Idol free so that we can deliver ‘a couple of cracking mixes’ to London. He’s shocked at the project halt, and can maybe see what’s coming more clearly than we are able to from the perspective of our besieged rat hole. He’s proposing a gonzo approach to mixing, not a new concept but a nice phrase for an exaggerated, over-the-top attitude.

The next call on the overheated telephone is from Stevo: ‘they’ve got you over a barrel and they’re waving the fucking dildo around. Not the nicest of images, but that’s what it is.’ It’s hard to see what this has to do with making a successful commercial record, so I have to speculate that some types might like fucking for the sheer pleasure of it. I also decide to donate quietly a couple of free studio days to the project (the charge is a steady $1000 a day, typically for more than 12 hours with the lights on and including all wages). There’s really no choice, even while taking a dim view of their apparent desire to can the project and their arrogant, distant communications. The show must go on.

If I have committed to record four tracks and mix two, they should also. A deal has two signatories. This is irritating and crass. Helpfully, by way of light, social relief, the three BETTYs arrive to redo their backing vocals on The Idol. Marc and I remember that recording can be fun. Why can’t we ever have team players at the record company? Why is it always so confrontational and antagonistic? Afterwards, late, I dine round the corner with Laura, my discreet lesbian assistant who is worrying about finally coming out to her parents. A bit of a strain all round, today.

All sorts of stories leaking from the studio are feeding the rumor mill. Chinese whispers are evolving overtime, although it’s nice to know that at least we are newsworthy to some people. Apparently, Mike Thorne has a serious drug problem. This is really getting exotic. Stringing a coherent sentence together, he tells both assistants to zip it, please, then goes back to the acid, speed, coke, smack, E, ludes, pot etc. The working week again extends into Saturday, another long one, but we have the extended version of The Idol laid out now. It’s all really sounding like a record.

After one short day off, Monday November 15 comes inevitably around, propelled by the alarm clock from the bottom of the sea. The New York company has found a new apartment for Marc on 14th Street. I finally talk to Steve Allen in London, and somehow manage to find some positive aspects of the last two weeks’ juddering.

Steve: They think I’m an animal around her, they don’t understand that Northern thing [he’s from Liverpool].

Me: Yes, but I could have done without the economic and political bumps.

Steve: Well it wouldn’t have been a kick then, would it?

Me: My ass is sore.

Earlier, management Mark had commented that ‘they’re just pulling our chain. Sometimes you just need to kiss ass.’ I’ve stopped trying to figure out the reason for all this aggravation. Others think it is a great record on the way yet we continue to suffer stumbling and incoherent discouragement from London. (From the perspective of 2005 and retirement from commercial production, it amazes me that such nonsense was so often the constant background noise to making records.)

After hours, I go to see Til Tuesday at the Bottom Line, enjoying their newly deconstructed version of Voices Carry, then clear off for beers with them at the Bleecker Street Bar. Aimee Mann is in familiar fractious and irritable mood, the others very sociable. We wind up staying out too late.

Mixing noise tests at studio with session setup accentuates the perfect morning headache. Sorting out time and logistics for January’s Carmel sessions in Liverpool is a further distraction, not to mention further discussion with Sandra Bernhard. When you’re working hard on a large body of music, it’s difficult to think of anything else, too easy to let other seemingly irrelevant tasks slip away as you progressively lose perspective on the outside world. I’ve had the lights turned out more than once thanks to the electricity bill moldering for too long under other less threatening mail.

Meanwhile, the politics continue. Ruby Marchand, the impeccable and musically encyclopedic head of Warner Music International’s A&R in New York, is shocked by hearing the story-so-far from me on the phone for the first time. Steve Allen hasn’t returned any of her calls. This doesn’t strike either of us to be a particularly effective way of facilitating Marc’s success as an artist in the US. Meanwhile, Harvey Goldberg is mixing away on the ‘rough’.

8 Politics, Clumsy And Cynical

This is all clearly getting to me. Wednesday night, I dream that I am back working in journalism, interviewing Blandanare Utu. He’s a former Grimsby Town soccer player sitting unshaven at home smoking himself silly and looking like a grizzled old coal miner. After our day’s work, the courier picks up at 5.30pm and we all decompress.

After recording the kids for The Idol, April 25 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

After recording the kids for The Idol, April 25 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

The following day, the political mystery-thriller progresses. Manager Mark has been told that there will be no more recording on Monday, since Steve didn’t give the go-ahead. Marc explodes once more, and says he’s on the next plane home. I call Steve at his home at 11pm London time and get another earful: ‘Other kids will crawl on glass to get to the studio, he’s self-indulgent, needs to call the WEA office to get a taxi to take him to the bank, I never bought a Soft Cell record anyway, Rob Dickens landed me with this project, Marc’s addicted to heavy tranquilizers, I’d get fired if anyone knew I’d told you this, I only found out from Rob and Stevo after I was on the case, anyway you can continue on Monday with the four songs, the discussions with Mark are about the next stage.’

This is getting positively existential. Marc and I talk at length about where we are, both of us increasingly exhausted and claustrophobic. Just to help things along, later at 11.45pm landlady Sandy calls and asks very nicely can we turn the drums down. Assistant Miguel is busy blowing it with a project session of his own, later crashing out of the building at 4am and waking up half the residents. Privileges withdrawn. This is getting to be more farce than any serious theatrical masterwork. Not to mention wildly distracting. Watch a cat in the garden on a windy day. It can’t focus for all the stimulus of stuff blowing around noisily, its head will jerk compulsively from side to side. Around me, it’s blowing a constant gale-force.

After Friday’s ructions, I send a fax to Steve Allen. The target is to finish the other two songs, Rise and Addicted, over the next two days. Marc sings a very good new Rise lead vocal. This is a tough piece, because both techno and heavy guitar elements are roaring flat out and compete ruthlessly for audio space with the vocal. Not to mention with the four trumpet parts. A more encouraging fax comes in from Steve, and a nice message from Ruby on the home phone machine mentions among other things that the US company is delighted with progress. But by Wednesday Marc has lost his apartment on 14th Street due to who knows what further record company snafu: administrative incompetence as a way of life. He loses more on the phone: ‘I’m going home, that’s it, the project’s over and I’m off Warner Brothers.’ Click. I call him back and point out soothingly that we’re very close to being able to do it on our own terms.

The Monday after the long Thanksgiving weekend holiday, Marc and I compare notes at studio. He’s lost confidence in some of the process and feels a need for a ‘musical mediator’. Paranoidly, I take it to mean I’m not solid enough, but then realize that he means we have had no constructive A&R sounding board at any time on this project. Seconded. I have always felt it so necessary and helpful to have a strong record company A&R presence, since provocation by a perceptive executive often pushes the music to another level. On this project so far, the overall reaction from the London company has been willfully confusing and/or drearily destructive. I dream of the constructive, team-like efforts with real company support and help, like the earlier Soft Cell albums in New York (Nonstop Erotic Cabaret, Nonstop Ecstatic Dancing and Torch).

But Marc is positive about going forward, favoring action rather than introspective analysis. We get going and soon the old optimism and energy kick in as we work on new material: To The Edge Of Heartbreak and Hurt To Love. We also start Lie, drawing inspiration from the immaculate Harthouse techno compilation from Frankfurt, Point Of No Return. A blast of that first thing in the morning will clean out the ears and toughen up the mind. On Wednesday, we commence Baby Night Eyes and Betrayed. Both of us feel as if we’re doing really good things. The following day, John Coxon shows up tired from London and provides useful closing insights on performance of a couple of songs co-written with Marc a few months previous. On Friday, Marc wants to do lead vocals immediately. All this is getting back to being fun. The two roughs in two days sound like finished records. We have also started Betrayed and Adored And Explored. This must be too good to last.

As usual, the alarm takes a few minutes to soak into my head the next Monday (December 7), after eleven hours’ sleep. I talk further to Carmel about her impending recordings, hear her worries about contemplating marriage, then return to the mechanics of piano practice and a few physical exercises, all for the first time in a while. Over a long project, it’s easy to let the physical side slip. At studio, I pour my first coffee slowly and thoughtfully, then put the milk back in the microwave. At least that’s cleaner than the dishwasher, where it sometimes goes.

Rick and Marc arrive, and we get going again. The next few days become a blur of creative music-making, with Chris Spedding finally arriving from LA on Wednesday to contribute many fluid and elegant rock+roll touches in his characteristically genial way. My notes for these sessions are endless details of successful musical additions and participants’ excitement at the progress. None of us feels tired. We stop early at 8.30pm, and Leila and I later talk over margaritas of, finally, a Caribbean holiday. It feels as if I’ve been recording this album all my life.

BJ Nelson singing on Out There, April 28 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

BJ Nelson singing on Out There, April 28 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

On Thursday we welcome BJ Nelson on backing vocals. She’s one of the top-rated New York session singers, deservedly so. We’ve worked together on many previous sessions after being introduced by engineer Carl Beatty when working together in Bedford-Stuyvesant on the Flowerpot Men sessions in the early eighties. As well as a great voice, she has boundless energy and I call her Captain BJ because of her dynamic arrangement and organizational abilities on session. Then, by Friday, we have seven more tracks in good shape and make a set of roughs that we think are impossible to argue with.

We’re all in great moods. Marc’s, unfortunately, has ended on Sunday when he calls me from the airport where a desk clerk is threatening to call security and have him ejected from the premises. He’s got no ticket and they don’t have one waiting, so he’s ‘bought a first class one and Warner Brothers will have to refund me’. The ticket agent is also losing it: ‘That’s Almond as in nut, right?’ Yes, it eventually transpires, he lost his ticket. But Marc is back in good shape when he calls on Tuesday after a meeting to play the roughs for Steve, who says, ‘this is the album I was hoping you would make.’ Steve plays Adored And Explored five times, and tells Marc that Betrayed is finished, not need to do any more, don’t spoil it, it’s perfect. He’s not worried about The Idol any more, the key track which has given us much difficulty, since he hears many more singles. Business job done.

Tuesday September 21st is my second day sick and in bed. Management Mark calls. He has heard from Francesca that the project is ‘on hold’ and that’s why I haven’t had my advance. I call Marc, yes he’s spoken to Rob Dickens who said that Steve was faking when he was enthusiastic in the meeting the previous week, and that ‘everybody hates it’. I’m utterly astounded. I call Marc a second time to tell him that whatever anyone says, I know it’s a great record, because I’ve been down this path before. ‘Don’t get worried when you look in the mirror. [If I’m feeling wobbly, I can only begin to imagine the concerns of the flagship artist.] None of it makes sense, so there must be a hidden agenda.’ And Steve must be a truly exceptional actor. This is getting really silly. How stupid do they think we are? But what I still don’t understand is the reason why.

The two of us know we can only be fatalistic about our predicament, since manager Stevo is in Sri Lankar on vacation away from a phone until January 10th. By now it’s becoming to seem more as if Rob Dickens is exercising some cynical maneuver for reasons I don’t know and without the slightest consideration for any of the dependent players, including his distinguished artist Marc Almond. Steve Allen is excused for just playing out his assigned puppet role, but is awarded a wimp sticker. Merry Christmas/Happy Holidays, everyone everywhere. Just keep all your heads down. Freeze your mood for a couple of weeks.

With typical thoughtfulness, we hear nothing directly from the record company, although some loose words at a London party are relayed to me by an embedded spy: the project will be restarting with me producing. On January 6th, I finally hear from Marc, who is in New York ‘until the weekend to pack up my things.’ He doesn’t fancy dinner, ‘too many things to do.’ Seems that he prefers to avoid the trauma zone. The days pass. So many people are trying to read the London tea leaves. Most interpretations are optimistic, but I’m not prepared to hang around and so confirm Carmel’s sessions and look forward to creative music-making with enduring friends. On January 20th I finally receive a long-outstanding advance payment from Warners. Thanks, and how about the next lump you owe me….?

I have a final conversation with Stevo on the phone, who thinks that the suggestion to dump all the music is ‘decadent’. I offer to finish the record to present it to others if, as I suspect, all this contorted nonsense is directed towards dropping Marc. Stevo: ‘If it comes to changing companies, my friend, never fear, never fear.’

9 Turnaround

It’s now February 9th, but the Liverpool weather is pleasantly sunny. Clive Black returns my call very promptly while I’m finishing up the sessions with Carmel at Parr Street Studios. He’s the new head of A&R at Warner Music London. Very friendly and constructive on the phone, the same productive and positive attitude as I remembered with pleasure from previous encounters. ‘Let’s sort this out, mate. They don’t understand what Marc is about.’ I’ll call him tomorrow on my return to London to fix up a discreet meeting, with him, maybe even sotto voce at my place.

A couple of weeks later, I’m waiting alone in the A&R Department’s common reception area with just mounds of unlabeled cardboard boxes and scattered posters for company. I keep my head conveniently buried in Melody Maker, and no-one registers my minimal presence. Clive and I have an intense, three hour meeting in his office, finishing late. He gets it all, and somehow it starts to make sense to me, off-the-record, politics being what they are. (Here, this reassuring and blunt exchange must therefore stay undocumented.)

The roughs sound astonishingly good in his office, even to my over-exposed ears, and he says that he must confirm with Marc but it sounds to him like a special album and that we’re really on to something. I leave his office ecstatic, feeling slightly unhinged through hearing constructive criticism and positive optimism after so many dreary, grinding months. Confirmation comes within 24 hours and I submit all budgets and options in a carefully-assembled four-page summary a few days later.

Recording the kids for The Idol, April 25 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

Recording the kids for The Idol, April 25 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

March 18th and we’re almost ready to start, but the paranoia hasn’t fully dissolved yet. Stevo calls: ‘I’ve got a bit of paper ‘ere that Marc wanted me to read you. “Neal will be coming over on April 7th, to do all guitars. There will be no more Chris Spedding on the album. We will start at 12 noon and work full five day weeks, no more four day weeks. I will be in New York for no more than two months.” ‘ So, Stevo, what’s the paranoia about? What’s behind this? ‘Dunno mate, look I talk to lawyers all day, I’m just passing it on, don’t shoot the messenger. I’ll get Marc to call you, ‘ang on ‘e’s on the other line.’ Now what’s going on? Best just to get on with the job and ignore such lumpen social behavior.

Five minutes later, Marc calls, even more upbeat and full of life than usual, and attitude far removed from the ponderous note I had been read. His first words are about being away to cure his addiction to sleeping pills and tranquilizers. He passes on the news (as Stevo should have if he were playing the definitive supportive management role) that Clive Black has approved everything for us to do: three new tracks with Neal, Looking For Love, and three live tracks with distinctive local artists.

It all sounds too good to be true. Stevo suggests to me quietly that the hidden agenda that I had guessed at could be to do with manipulating publishing conditions since if Marc delivers a specific number of tracks on time, all publishing reverts to him (otherwise it remains with the publishing company). Big business above all. Which has blighted our existence for months and, without our dogged persistence, would have seriously compromised the music which is supposed to be its raw material. We have been cannon fodder.

I’m so glad that Clive is on board, but will never forgive Warner Bros (now seemingly in the form of Rob Dickens) for cynically compromising our quality of life and work for so long. None of this can have been helpful to Marc’s physical and mental states, and could have driven other less resilient characters into a really bad place. I assure Marc that his previous chemical condition didn’t affect anything, that it has been a pleasure working with him at all times, and that I am impressed he’s held it together so consistently. Both of us are very excited at this new restart, and at the conclusion of this fresh, innovate heap of music. Almost too hard to believe.

10 Back At Work

Off we go again on Monday March 21st. The studio is a flurry of musical activity all week. Plans for the remaining tracks and the project completion gel briskly, and we plot to collect John Cale, Chris Spedding and David Johansen (ex-New York Dolls and now successful in his solo career) for a live session. The other elements are to be just a drum machine, and Marc singing live. The drum machine/guitar/grand piano (John) and harmonica (David) combination sounds like a nice, organic counterpoint to the other electronic material. By coincidence, John stops by the studio to borrow a microphone. He’s around and available. A few more calls and the downtown New York supergroup is ready to go.

I arrange with Harvey Goldberg that he will be the mix overseer. I’ll start, and get it to where I like it, effects and all. He will come in and critique and adjust. I’ll come around again, then when we have something we like we’ll print it. Sounds like a way to get all our talents focused and nobody bored. Another long-term engineer associate, Carl Beatty, is now a professor at Berklee College of Music and arrives at the studio with a crocodile of students in tow which winds up in the evening watering at what was Mediasound at 311 West 57th Street. We think about exorcising the Soft Cell ghosts from Studio C, where we recorded the bulk of their first two albums, but such has been the remodeling to create Le Bar Bat that we can’t even work out where it might have been. Soft Cell really was a long time ago. Mediasound, founded by the two inspired people behind the Woodstock festival, had ceased music functioning in the mid-eighties.

Recording the kids for The Idol, April 25 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

Recording the kids for The Idol, April 25 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

For the next two weeks, my notes are just further mundane details of assembling the album in a heady, creative rush. Neal is in from London again, a welcome and cheerful presence, and Rick is always dropping by for a guitar overdub or to give encouragement. There are also notes about frequent constructive phone interchanges with Clive in London. And also about some ambitious sonic experiments, of which a few work spectacularly. An extraordinary guitar performance derivation on the new Child Startakes four hours to realize, and is a beautiful arrangement unlike anything else I’ve heard. (Stevo tells me later that when he first heard it, ‘I cried.’) All this smooth and successful progress makes for rather boring reading.

One song, co-written by Marc and Neal, is created largely from scratch in the studio: Brilliant Creatures. It starts with a pure germ of an idea, the chords evolving through Neal over a couple of hours. Over the next week it will establish itself as one of the most passionate and distinctive pieces of the album. The Idol hasn’t been forgotten, and we try BJ Nelson on chorus backing vocals.

Marc wants children to sing the chorus, but I’m a little leery of its sounding a little too knowing by introducing such naïveté. But, meanwhile, we’re so relaxed about it because we seem to have perhaps five singles on the album which all sound distinctive and different while being uncompromisingly accessible. The present core team of four, with Neal and Rick, is working so smoothly and energetically that it feels almost like a group thing. Neal’s hangover after a night out with Rick is groundbreaking and entertaining.

The big session is on Friday April 8th. At 8am I wake up with hair standing on end, having forgotten to tell the studio about equipment we’re sending over. The Dolby SR (a tape noise-reduction system) takes quite a while to set up and align. And I haven’t faxed them the session layout sheets as promised. Logistics have taken considerable working out, preparing for a session which will be over in just five hours. It’s a bit like a string section session, where you labor for a long time off-line to create the arrangements. Then the 16 or so musicians come in, contribute to the song for maybe an hour, and you’re left gasping for breath after so much music gels in so short a time.

I’m at Skyline Studios (like Mediasound, also now defunct) by 11.30am. John Cale has left messages both at home and at studio. Sounds concerned. Maybe he’s really messed up his schedule (he’d been asking to shift the date already). Call him. ‘I haven’t listened to the tape.’ That’s the least of his worries, and I tell him so. ‘Just get over and I’ll give you the chord sheet.’ After producing an album for him twelve years earlier, I know that’s a good place to have him, edgy and spontaneous, under threat and having to be brilliant NOW. As he can be. He arrives earlier than required. Still edgy but very friendly. Chris shuffles in 15 minutes later, the mellowest of all but very capable of waking you up instantly with his guitar, followed shortly by David and Marc.

We’re recording three songs in the old-style 24-track manner, Come In Sweet Assassin, Sacrifice, and Violence. (Could there be a common theme here? These sound like classic John Cale/Velvet Underground titles.) They’re all based on the steady drum machine which can be replaced or refined later in response to whatever happens to the music today. After transferring to a hard disk recorder, anything played now can be slipped in time to any part of the piece, or even repeated as desired. This means I can encourage everyone to be loose and adventurous since, unlike conventional recording to fixed 24-track tape, one mistake will not spoil a take. You can fall at a hurdle and recover. It’s perversely productive: with the non-linear digital editing: we can collect all the good bits and even exploit inspired mistakes. This is very positive. Especially with such spontaneously brilliant people.

During Sacrifice, aka Kiss And Die, the news comes through of Kurt Cobain’s suicide. He’s blown his head off with a shotgun. It’s another of those coincidences, and the room goes quiet as a few people reflect. It could have been one of us, landing in that desperate place. Later, the tape runs out just before Violence has come to the end of its initial, great take (it does sometimes happen), but we can remedy this disaster thanks to the non-linear disk editing. That assistant engineer’s mistake would certainly have spoiled the party in earlier technological eras, but now we can declare the music butterfly caught securely in the net.

John Cale getting into Violence, April 8 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

John Cale getting into Violence, April 8 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

John clearly has a dinner engagement, since he hurtles off into the night as soon as we’re done. He can’t speed up the drum machine by playing the piano any faster, fortunately. I’m reminded of legendary conductor Thomas Beecham’s being asked after one Promenade Concert night in London why he had taken the last movement of a symphony at such high tempo. ‘The call of nature, dear chap’ he is reputed to have replied. David and Chris remain to overdub some parts and socialize. Someone once said of David that, like Mick Jagger, his soul is really in his harmonica, rather than for what the world knows him. As for Chris, he delivers an effortless flamenco-accented line which takes Violence another step up. We wind down listening to David’s new album from his reference cassette, then drift off around 9pm.

None of these tracks will remain in the form in which they were played. There’s a new way of manipulating music, comparable with composition. There’s a new skill in looking at all the musical material which has been played within a song framework and to a loose plan, to see if there are further, more exciting structures possible given the players’ directions on the session. You can find some very new things this way. It’s a long way ahead of (and far more difficult to pull off than) the smaller-scale sample-based method of making commercial music which predominates today.

11 Career Turn

For me, there is a total change of direction defined on Saturday. I want out of record production, and have done since the end of 1993. I’ve had enough of hired-gun production and politically negative experiences, of which this album project already has far too many. I’m missing creative trouble. In the old days, the record company would just pat you on the head and say, ‘bring us back a good record. Call us if you hit problems.’ I started in production working with left-field, unpredictable characters with wild ideas, not conveniently regressive, statistical smoothies playing with legalese. I don’t want to devote the rest of my life exercising hard-won expertise on bland, mass-market derived agendas. Stimulating trouble seems to have been run out of town, too dangerous to have around.

All my hits have been with artists with a distinctive style and disposition. Many hits I’ve delivered sound like nothing else. I’ve become bored with being asked to deliver a hit to a marketing specification, a syndrome which just crept up on me. Like the frog in the slowly-heating kettle, I hadn’t noticed the temperature rising in time to jump out. I’m not finding enough trouble (that’s a different kind of trouble from the garbage that has been dumped on Marc and me for the last seven months), so I have been in touch with Ramon Lopez, Chairman of Warner Music International. He is not just Rob Dickens’ boss, he is the boss of Rob Dickens’ boss, and he has invited me to a meeting in his weekend digs at the St Regis Hotel. We discuss CD-ROM and coming technological upheavals. I get home. Ramon’s ideas for a corporate role are challenging, promising new exciting exploration for me. Sounds like the missing madness.

This weekend, Leila and I are buried in family. She says, ‘it sounds like you’ve just been offered a job.’ I now know that this will be my last commercial record production. It will be wonderful to retire with this creative artifact which is among the best that either Marc or I have done, together or independently. It feels in the bag. And it will be perfect to move on when at the top of my craft. Closure seems to be coming very tidily in several different areas.

April 11th, and on this new Monday we’re preparing for Clive Black’s arrival in New York tomorrow. Marc has a stinking cold and is jumpy. Recently, he seems to spend every other morning yelling at Stevo on the phone. I spend most mornings just trying to come around with the aid of strong coffee and loud Harthouse techno, which continues to be an inspiration.

Thanks to being hired by Ramon, I will meet the intense people behind Harthouse, two years later at the label Eye-Q in Frankfurt. I still have their inspired Recycle Or Die steel (recycled) plates and CDs on my wall at home. The label would call it quits in 1997. They effectively went the same way as I did when marketing began calling all the shots for the artists and it didn’t work. In April 1994, I didn’t know that this passionately favorite project (again, what I thought was possibly the best work Marc and I had done anywhere) would collapse under parallel pressures. Worldwide, musical risk-takers were, unknowingly, facing the same increasingly limiting and suffocating issues. It’s the world we live in just now.

After techno, cold remedies and a diatribe or two, the music continues to flow, the more so as we smell completion. The last days of any album are always an extreme rush: you’re under deadline pressure but you tap into the warmth and bottled energy coming off all that earlier effort and construction. Final ideas settle in with the benefit of immediate perspectives and places. It’s such a different experience from starting out with the blank sheet of paper. At last, the musical logic crystallizes.

12 Finishing Up

There is, however, one very significant piece of unfinished business. The Idol is clearly working musically, but we haven’t got the chorus atmosphere quite right. None of the attempts at backing vocals, ‘we love you, we love you, we hate you, we hate you’ answering the pop idol protagonist’s verses hit the spot. I have been cautious about pulling in young kids to sing the words, complaining to Marc that it verges on sleazy, and we have to shield young minors from some harsh realities of later life. Marc takes great offense to ‘sleazy’, pointing out that it is the character who is off-color. He’s right, although I say, ‘it might not be easy telling that to the parents.’ But I’ve learned to trust him musically before, to rely on instinct when words don’t articulate a specific idea.

David Johansen recording Adored And Explored, Wednesday April 27 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

David Johansen recording Adored And Explored, Wednesday April 27 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

The logistics of recording children include a few more issues than for older people. They’re clearly mostly non-union, and all need parental or guardian’s consent for anything they do. And, of course, they’re little-trained (although that’s usually the reason for pulling them in). Marc and I think about ‘recording’ them at the Camden Cell studios, ducking local restrictions by using this virtual studio in my former house’s basement in London at 37 Camden Park Road where Soft Cell’s first two albums were supposedly recorded.

After much creative thought between us, I call the local Musicians’ Union Local 802. No problem, they say, just pay them properly. I recall one prominent New York musician slamming down the phone in the control room during one session: ‘God, I hate the union even more than the phone company.’ It’s refreshing to hear such a non-restrictive (constructive) response. I call Sandra, a teacher friend on our block, and off we go with local brats including her son.

Come Thursday, Marc has turned down the offer of recording a quick, simple but turgid single for the remake of Sunset Boulevard. He’s meanwhile very concerned about his per diems (living support) in New York, and is still in the middle of his maddening home renovation in London. I’m impressed by his integrity in leaving a pile of money on the table, thinking it takes some guts to do it. Clive Black, still in New York, stops by the studio again, but this time while Marc is singing the lead vocal on Looking For Love. That’s really putting him on the spot, but after a short swallow and a deep breath he delivers the passionate master.

Later on the phone, Marc teases me, ‘you shouldn’t hear this.’ I say that I’m sitting down. Chris has told Stevo that he doesn’t care what anyone says, Mike Thorne is a genius and this album is so full of hooks. After just a short hesitation while I wonder who ‘anyone’ might be, I say, ‘well that’s two of us on the session, like the attitude.’ Compliments are now set to go over the top, as we sort of know, and the buzz is growing fast. This tastes good, finally. It feels as if we are approaching, after surviving enormous adversity, the delivery of a classic record. We have reached our difficult goal of a passionate record with a brand new sound and style, the mix of tough guitars and techno working wonderfully in a way no-one has heard before.

Back to earth with Violence, a song whose lyrics don’t shirk the issue. Marc’s burnt with thinking about it and is ready to ax it, even getting irritable about John Cale’s piano ‘because he was off to a dinner party’ (I now regret making that crack about John’s exit from the session). His mood is swinging too much for objectivity, so he leaves me to the electronic deconstruction of the song.

Working with music in this way can feel like juggling with too many balls in the air, but I get on with it. Marc eventually returns with Rick and everyone is happy. This has morphed into an extraordinary track. We now seem to be coming up with utterly different (but powerfully effective) musical gestures on a daily basis. At 11pm, Stevo calls (‘You’re up too late’), concerned about the meetings with Clive at the studio, but he sounds confident almost mellow, which is perhaps as well after suffering Marc’s tirades over the past few mornings.

April passes quietly and constructively, one small, necessary solution after another being routinely achieved. We have a huge amount of music here, well over an hour, not even including the extended version of The Idol nor the alternative, extended version of Risewhich we will create right at the end of the project. The last real fun happens when the kids turn up to sing after school on Monday 25th.

Marc and I are more nervous than if we’re expecting a big string section. When they arrive, these downtown New York kids are not the shrinking violets we remember being at age 13 when growing up on opposite coasts of the North of England. After just five minutes’ acclimatization they’re off. Although the climactic line ‘sweet crucifixion’ makes us both wince, the parents in the room are perfectly content, the children working excitably with their short schoolyard attention span. Seemingly effortlessly, Marc puts them completely at ease, expertly guiding them and nurturing their performances. Teacher Sandra is impressed, and comments that Marc could have another vocation.

After the vocals are done, the final touch on a perfect track, we have a special treat for Dylan and Nina when we record their own song directly to cassette. Then we do the big track playback where everyone goes ‘wow’ when we show them delays. Daisun says, ‘I could do that,’ so I let them all loose on the mixing board (after they wash their hands). An interesting final production, although not quite what Marc and I had in mind.

David Johansen and Chris Spedding on the Skyline session, April 8 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

David Johansen and Chris Spedding on the Skyline session, April 8 1994, photo: Jo Dawkins

We start mixing, finally, on Tuesday May 10th. It’s now seven long, bumpy months since the start of the project. My previous productions have usually taken around ten weeks, including rehearsal, preproduction, mixing and two weeks’ sunny interlude holiday.

We finish the mixing towards the end of May, which is when my detailed journal finally ends. I feel I have documented a singular and successful project. This can inform a unique book which can also include essays on related aspects of record production. Right at the end, I fax Stevo asking him if I can give a cassette to Ruby and Thelma, but he says that he would prefer Warner International not to get too interested (as A&R man Dave Bates is announced in his office calling on the other line). Sounds like Phonogram is the new home for the album.

13 Label Change: Plus Ca Change

At this point, I’m doing double duty, moonlighting to learn more about CD-ROM authoring and interactive design techniques while waiting for the job position to be set up. I’m heading for a new, stimulating crazy zone, after the musical one has apparently dried out, and it’s tough to get the bearings. Phonogram is eventually confirmed as the new record company. Clive Black is understandably very upset at the loss of a special project through cynical business manipulations. He will leave Warner Music shortly afterwards.

And the relationship with the new label is off to a wobbly start. The condition of payment at the back end of the production is that multitrack tape transfers of all our tracks are delivered to London. Manager Mark Beaven’s enquiries reveal that possibly the whole album might be remixed by as yet unknown characters. This sounds awful. In the early nineties, too much music production is becoming driven by style rather than content. Fewer people listen with their ears. This sounds like following the herd, not like a strong business plan tailored to a special and distinctive album.